(January 12, 2026) Gandhi’s January 1915 homecoming, commemorated as Pravasi Bharatiya Divas, is one of the most powerful examples of how experiences abroad and a return home can change a nation’s course.

111 years ago, in January 1915, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi returned to India after more than two decades abroad. He had left as a young man in search of education and work, and came back shaped by years of struggle, reflection, and resistance lived far from home. His return was not the end of a journey, rather the beginning of a larger one.

On January 9, 1915, as a ship from England approached Bombay’s shoreline, the moment carried a weight that history would later recognise as transformative. Gandhi who was not yet the Mahatma, and not yet the leader of India’s freedom struggle was received with unusual attention. Among those who came to welcome him were Bombay’s prominent industrialists, a senior doctor, a diamond merchant, and a journalist.

He had left India in the 1890s as a young barrister seeking work in South Africa. He was now returning with his wife Kasturba, without power, wealth, or official position, yet was already well known back home for confronting injustice, organising migrant communities, advocating for the rights and dignity of Indians abroad, and refining a method of resistance that rejected both submission and violence.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and Kasturba Gandhi after their return, at their first public reception in Bombay, hosted by philanthropist Jehangir Petit on January 12, 1915

Bombay responded instinctively. Over the next one week, from January 9 to January 16, the city would welcome Gandhi with receptions, speeches, meetings, and tributes. The first major gathering came on January 12, at the Peddar Road mansion of Jehangir Petit, where nearly 600 people assembled to hear the man many believed represented a new kind of leadership.

His reputation preceded him, and his journey mirrored what many Indians abroad were experiencing by learning through hardship. He had come back with hard-earned insight that mattered at home. It is for this reason that the day of his return is today commemorated as Pravasi Bharatiya Divas.

The departure that began it all

Gandhi’s journey began not with politics, but with aspiration and uncertainty. In August 1888, an 18-year-old Mohandas Gandhi left Porbandar for Bombay, and from there sailed to London to study law. For a young man from coastal Gujarat, it was a leap into an unfamiliar world socially, culturally, and intellectually.

London shaped him in subtle but lasting ways. Between 1888 and 1891, he trained in law at one of the city’s historic Inns of Court, the Inner Temple, learned discipline through restraint, and confronted a challenge that many Indians abroad still recognise: how to engage with the West without surrendering one’s inner compass. When he returned to India as a qualified barrister in 1891, success did not follow. His law practice faltered, and by 1893, another overseas opportunity presented itself. It was the one that would completely transform his life.

That year, Gandhi travelled to South Africa to assist an Indian merchant in a legal dispute. It was meant to be a short professional assignment. Instead, it became a 21-year immersion in injustice, resistance, and self-discovery.

South Africa: Where a lawyer learned to resist

South Africa confronted Gandhi with a harsh truth that many migrants encounter early: qualifications do not shield one from prejudice. Almost immediately after his arrival, he faced racial humiliation, most memorably when he was removed from a first-class train compartment despite holding a valid ticket. That night, stranded and shivering at Pietermaritzburg station, Gandhi made a choice that would echo through history. He would not retreat. He would resist.

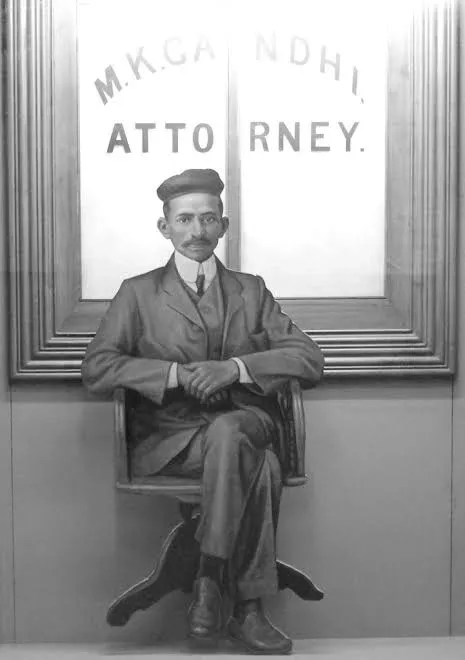

Mahatma Gandhi during his younger days as a lawyer abroad

Between 1893 and 1914, Gandhi evolved from a cautious lawyer into a public figure shaped by struggle. He organised Indian communities scattered across South Africa, challenged discriminatory laws, endured repeated arrests, and refined the philosophy that would define his legacy of satyagraha, the insistence on truth through nonviolent resistance.

South Africa became Gandhi’s leadership laboratory. There, he learned how to mobilise ordinary people, how to communicate across communities, and how moral consistency could become a political weapon. His activism gave voice to a marginalised diaspora and demonstrated that Indians abroad could assert dignity without replicating the violence of empire. He even founded Indian Opinion, a journal that reported on the lives of Indians in South Africa and India, while engaging with social, moral, and intellectual issues.

Just as importantly, Gandhi learned to scale abroad and how small, vulnerable communities could act with collective strength. India would later show him how far those lessons could travel.

By the time Gandhi left South Africa in 1914, his health had suffered. A severe bout of pleurisy took him to London for treatment. Doctors warned that the English winter would worsen his condition and advised him to return to India. Around the same time, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, a key leader of the Congress Party, was in touch with Gandhi, urging him to come back. This time, it would not be a visit. It would be a homecoming.

January 9, 1915: An arrival that changed everything

On the morning of January 9, 1915, Mohandas Gandhi arrived in Bombay with his wife Kasturba aboard the S.S. Arabia, a mail boat from London. The reception was unusual because the man was unusual. India already knew him as someone who had challenged racial injustice abroad, endured prison, and returned without bitterness.

He remained in Bombay for a week before travelling to Ahmedabad. In that brief span, the city embraced him as both a moral curiosity and a returning hero. The seriousness with which he was regarded was unmistakable. He met Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, and a steady stream of relatives, admirers, and political figures. At a gathering organised by the Gurjar Society of India, Jinnah delivered a long speech in English praising Gandhi and Kasturba, followed by Gandhi’s equally measured reply in Gujarati.

Perhaps the strangest moment came when he was presented with a set of golden shackles, intended as a symbolic tribute to his imprisonment in South Africa. Gandhi’s response was characteristically blunt. Fetters, he said, whether made of gold or iron, remained fetters all the same.

Already known, not yet leading

His correspondence with Gopal Krishna Gokhale and the Indian National Congress during his South African years had ensured that his work was closely followed. Yet he was not yet the leader of India’s freedom struggle. Gokhale, recognising both Gandhi’s potential and the risks of premature politics, made him promise not to plunge into active political leadership for at least one year. Gandhi agreed.

In interviews shortly after his arrival, Gandhi explained that having lived abroad for so long, he needed first to observe and understand India anew. He described himself as a student, not a commander. The British, too, were watching, but they did not yet consider him dangerous. That misjudgment would prove costly.

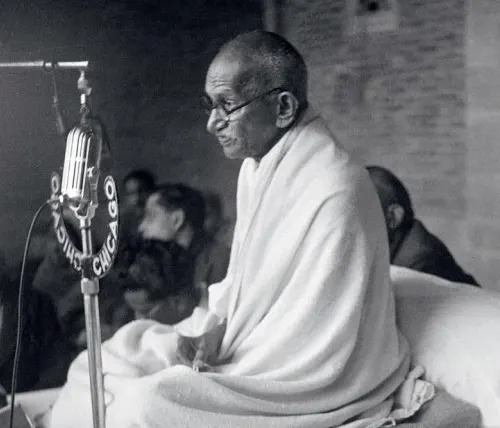

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and Kasturba Gandhi

From observer to organiser

True to his word, Gandhi spent his early years back in India travelling, listening, and learning. When he finally acted, it was with precision. In 1917, he took up the cause of indigo farmers in Champaran, marking his first major political intervention in India. It was a modest beginning, but it demonstrated the power of his method.

Over the next decade, Gandhi transformed Indian nationalism. By 1921, he had become the central figure of the Indian National Congress, reshaping it into a mass movement rooted in moral participation rather than elite negotiation. His campaigns for swadeshi, social reform, and self-rule gave ordinary Indians a sense of agency.

The Salt March of 1930, which was a 24-day walk from Ahmedabad to Dandi cemented his place in global history. A simple act of making salt became a challenge to imperial authority, watched by the world. Gandhi had succeeded in turning ethical protest into a universal language.

A global figure, grounded at home

Even as he led India’s struggle, Gandhi remained a global conscience. His ideas influenced civil rights movements worldwide, and his commitment to nonviolence resonated far beyond India’s borders. Yet his final years were marked by sorrow with the Partition, communal violence, and the moral agony of seeing freedom arrive fractured.

When India gained independence in August 1947, Gandhi did not celebrate. He walked through riot-torn regions, fasting and pleading for peace. On January 30, 1948, he was assassinated, but his legacy had already crossed continents.

Why Gandhi’s return still matters

January 9 is commemorated as Pravasi Bharatiya Divas for a reason. Gandhi’s return from England, carrying the lessons of South Africa reminds us that the highest expression of the diaspora journey is not accumulation, but contribution.

He went abroad seeking opportunity. He grew through adversity. And when he gave back, he changed the course of history. 111 years later, Gandhi’s life still poses a timeless question to every Indian abroad. And the question is, ‘What will you bring back from the world?’

ALSO READ: Gandhi’s ally in South Africa: How Thambi Naidoo led the Indian diaspora’s fight against racism