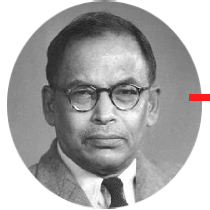

Meghnad Saha’s experience is a testament to human potential. Born on October 6, 1893, to a poor Bengali Hindu family in a small village in Dacca district (now in Bangladesh), he became one of the world’s most prominent scientists of his time. His parents, Jagannath Saha, a poor shopkeeper, and Bhubaneshwari Devi, raised him as the fifth of eight children. His story shows how determination conquers adversity. Despite his lower-caste background, Saha’s brilliant mind helped him achieve academic excellence, and he ranked third in the ISC examination in 1911.

Saha’s most important contribution came in 1920 when he developed the thermal ionization equation that changed astrophysics. Scientists have used this equation to interpret stellar spectra and find the chemical composition of light sources. The Royal Society recognized his brilliance by electing him as a fellow in 1927. He later served as president of the 21st session of the Indian Science Congress in 1934. His legacy includes several scientific institutions that he built, including the Department of Physics at Allahabad University and the Institute of Nuclear Physics in Calcutta in 1947.

CEO’s | Actors | Politicians | Sports Stars

Saha’s impact reached far beyond pure science into public service. The newly independent India saw him win election to the Lok Sabha in 1951 with a commanding 16% margin. His life stands apart from other distinguished scientists of his time. He rose from poverty and social constraints to shape both scientific progress and national development. This piece explores how a village boy became a legendary physicist by learning about his education, discoveries, political involvement, and lasting impact on Indian science.

From a Village in Bengal: Meghnad Saha’s Early Life

Humble beginnings in Seoratali

The birth of a genius: Meghnad Saha came into this world in the small village of Seoratali, in the Dacca district of undivided Bengal (now Dhaka, Bangladesh). This remote hamlet, just 45 kilometers from Dhaka city, saw the birth of one of India’s greatest scientific minds on October 6, 1893. Seoratali wasn’t just a spot on the map. The village shaped Saha’s early worldview and determination. No one could have guessed that this simple rural setting would produce a physicist who would change our understanding of the stars.

Rural roots and early environment: Seoratali’s landscape painted a picture of lush green paddy fields and simple mud houses where Saha spent his childhood. Rural Bengal was still healing from the devastating famine of 1876-78. Millions had died, leaving deep economic scars on the region. Life was basic here. The village had no electricity and barely any educational resources—the kind of place that usually limits a child’s academic future. Yet young Meghnad’s exceptional curiosity and intellect made him stand out from other children his age.

Family background and caste discrimination

The shopkeeper’s son: Meghnad was the fifth of eight children in a struggling family. His father’s small grocery shop barely fed the large household. Jagannath Saha worked hard while Meghnad’s mother, Bhubaneshwari Devi, ran the home and cared for the children under tough economic conditions. The family’s Shudra caste identity, specifically from the “Koiborto” (fisherman) community, placed them among the lower rungs of Bengal’s Hindu caste hierarchy. This social position would create big hurdles in Saha’s educational path.

Facing the caste barrier: India’s rigid caste system in the early 20th century left few doors open for lower caste individuals. Meghnad faced rejection from several institutions that denied him hostel residence purely because of his caste. Presidency College’s Eden Hindu Hostel initially turned him away—a rejection that stuck with the young scientist. Yet these setbacks only fueled his drive to prove himself through academic excellence and scientific achievement.

Early schooling and Swadeshi movement involvement

First steps in education: The village primary school marked the start of Meghnad’s formal education, where everyone noticed his exceptional abilities quickly. His father saw his son’s potential and made his education a priority, despite money troubles. Seven-year-old Meghnad joined Dhaka Collegiate School, but a plague outbreak forced a change. He moved to Dhaka Collegiate School and later to Dhaka Government School (now Dhaka College). Math and sciences came naturally to Saha throughout these early years.

Awakening political consciousness: Bengal’s political scene heated up in the early 1900s, mainly over Lord Curzon’s 1905 Partition of Bengal. Young student Meghnad dove deep into the Swadeshi movement—a nationalist boycott of British goods that was part of India’s independence struggle. His protest activities got him expelled from school, proof of his courage and conviction at such a young age.

The foundation of scientific curiosity: Politics and social barriers couldn’t dim Saha’s passion for science. He got his hands on old textbooks and scientific journals, often studying by kerosene lamplight late into the night. Teachers noticed his gift for solving tough math problems in creative ways. These early years built not just Meghnad’s academic skills but also his never-quit attitude that would mark his later scientific career.

The village boy’s path to becoming a world-famous physicist started with these early challenges. Growing up in a remote village, pushing against caste discrimination, and finding his political voice made Meghnad Saha more determined to succeed against all odds.

Education Against All Odds

Struggles at Dhaka Collegiate and Jubilee School

Political awakening at a cost: Meghnad Saha’s educational trip hit its first major obstacle in 1905. Political unrest swept through Bengal that year. He got admission to Dhaka Collegiate School and joined the boycott of British Lieutenant Governor Bampfylde Fuller’s visit during the Swadeshi movement. The school expelled him immediately and canceled his scholarship. This early brush with politics shaped his nationalist thinking, though it disrupted his studies.

Resilience amid setbacks: Saha bounced back quickly. He joined Kishorilal Jubilee School and his intellectual abilities thrived. His hard work paid off in 1909. He scored the highest marks in Bengali, Sanskrit, English, and Mathematics in the Entrance Examination. He ranked first among East Bengal students and third in all of Bengal. His academic success continued at Dhaka College. He ranked third in the ISc examination in 1911, while his future colleague Satyendranath Bose took first place.

Academic excellence at Presidency College

A stellar academic trajectory: Saha moved to Kolkata in 1911 to study at the prestigious Presidency College. He earned his BSc in Mathematics with honors in 1913, finishing second in his class. His mathematical talent drove him to pursue higher studies. He completed his MSc in Applied Mathematics in 1915, again ranking second to Satyendranath Bose. His academic performance remained outstanding throughout college.

Distinguished classmates: Presidency College buzzed with exceptional talent during Saha’s time. His classmates included future pioneers like Satyendranath Bose (known for Bose-Einstein statistics), Nikhil Ranjan Sen, Jnanendra Nath Mukherjee, and Jnan Ghosh. Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, who later founded the Indian Statistical Institute, studied one year ahead. Freedom fighter Subhash Chandra Bose was a year junior. This concentration of brilliant minds created an environment perfect for intellectual growth.

Influence of mentors like J.C. Bose and P.C. Ray

Guidance from giants: Saha learned from India’s finest scientific minds at Presidency College. His professors included Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose, Sir Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray, Professor DN Mallik, and Professor CE Cullis. These pioneers shaped Saha’s scientific thinking and outlook significantly.

Beyond academic instruction: Prafulla Chandra Ray’s influence stood out. Though Saha studied mathematics, Ray’s guidance went beyond chemistry lessons. Yes, it is these Presidency mentors who inspired Saha to see science differently. He viewed it as a tool to promote nationalism and revive ancient India’s intellectual legacy. This vision guided his later work and institution-building efforts.

Facing caste bias in student hostels

Systematic discrimination: Saha’s education came with painful experiences of caste discrimination. Upper-caste students at Eden Hindu Hostel refused to eat in the same dining hall with him because he belonged to the Shudra caste. This wasn’t just random prejudice but systematic exclusion.

Religious discrimination: Brahmin students blocked Saha from making offerings to Saraswati, the Hindu goddess of learning. The social barriers hurt him deeply but strengthened his determination. He believed that merit and intellect should exceed caste boundaries. This progressive thinking was way ahead of its time.

The Breakthrough: Saha Ionization Equation

What is the Saha equation?

A mathematical masterpiece: Meghnad Saha developed his groundbreaking thermal ionization equation in 1920. We now call it the Saha Ionization Equation. It shows the relationship between a gas’s ionization state in thermal equilibrium with temperature and pressure. This equation brings together quantum mechanics and statistical mechanics beautifully. It describes how atoms inside stars become ionized under extreme heat. The equation connects the number density of atoms in different ionization states and takes into account temperature, electron density, and ionization energy.

The fundamental principle: Saha’s equation helps us understand how gasses behave at stellar temperatures. It reveals the ionization degree of any gas in thermal equilibrium by showing its relationship with pressure and temperature. The equation proves that atoms lose more electrons as temperature rises, especially above the ionization energy threshold. This process turns ordinary gas into plasma—which many scientists call the fourth state of matter.

How it changed astrophysics

From qualitative to quantitative science: Astrophysics lacked quantitative tools before Saha’s breakthrough. His equation turned the field into a numbers-based science. Astronomers could now interpret stellar spectra with mathematical precision. Arthur Stanley Eddington ranked this work among the most important discoveries in astronomy and astrophysics since Galileo invented the telescope in 1608.

Resolving stellar mysteries: Scientists couldn’t explain why similar elements created different spectral lines in various stars. Saha showed that conditions within celestial bodies—not just their elemental makeup—determined which spectral lines appeared. This finding cleared up much confusion about physical conditions in stellar atmospheres during the early 1900s.

Applications in stellar spectroscopy

Decoding stellar composition: Saha’s equation serves as the foundation for interpreting stellar spectra. Astronomers use it to find both star temperatures and element ionization states. This knowledge helps us understand how stars evolve and what they’re made of.

Stellar classification breakthrough: The equation’s most important use explains the OBAFGKM spectral classification of stars. Scientists found this sequence shows how elements ionize and excite at different temperatures. Saha’s equation also explained why giant stars and main sequence stars at the same temperature have different ionization patterns due to pressure variations.

Recognition by global scientific community

Scientific validation: Scientists worldwide saw the value of Saha’s work quickly. Ralph H. Fowler and Charles Galton Darwin confirmed his equation with more detailed derivations. Edward Arthur Milne and Fowler built on Saha’s work in 1923. They showed new ways to determine physical parameters of stellar atmospheres.

Near-Nobel recognition: Saha never won the Nobel Prize, but scientists call his ionization equation “in the Nobel Prize class”. His work ranks among the top achievements of 20th-century Indian science. Today, students worldwide learn his equation in statistical mechanics and thermodynamics courses. Meghnad Saha’s mathematical insight helped us understand the stars better than ever before.

Beyond Science: Politics, Institutions, and Vision

Founding the Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics

Institution builder: Meghnad Saha established the Institute of Nuclear Physics in Kolkata in 1943. Irene Joliot-Curie formally inaugurated this trailblazing establishment on January 11, 1950. The institute later became known as Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics. His vision transformed it into a research hub for applied nuclear physics, biophysics, crystallography, and many more scientific disciplines.

Role in Indian Parliament and planning commission

Political representative: Saha won election to Parliament as an independent candidate from the Calcutta North-West constituency in 1952, after retiring from the University of Calcutta. His campaign funds were so limited that he asked his textbook publisher for a ₹5000 advance. He strongly supported educational reform, scientific research funding, and rational industrial planning during his time in Parliament.

Views on science and national development

Development visionary: Gandhi focused on village-based development, but Saha believed large-scale industrialization would reduce unemployment and achieve national self-sufficiency. He convinced Subhash Chandra Bose, then President of the Indian National Congress, to establish the National Planning Committee in 1938, with Jawaharlal Nehru as its chairman. Saha consistently believed universities should serve as “fountainheads of knowledge” where fundamental research could thrive.

Involvement in river valley and calendar reform projects

Scientific solutions: Saha’s childhood experiences with flooding in the Brahmaputra delta sparked his deep interest in river physics. He and Kamlesh Ray studied international flood control systems extensively and worked with Dr. B.R. Ambedkar to establish India’s first multipurpose river valley initiative – the Damodar Valley Corporation in 1948. The government appointed him chairman of the Calendar Reform Committee in 1952. He studied over 30 local calendar variations and recommended a unified national calendar that India officially adopted in 1956.

Legacy of a Revolutionary Scientist

Legacy of Brilliance

Meghnad Saha’s exceptional trip from a small Bengali village to the heights of scientific achievement shows evidence of intellectual determination against huge odds. He faced caste discrimination and money problems. Yet he changed astrophysics with his groundbreaking ionization equation. His mathematical formula ranks among the ten most important astronomical findings since Galileo. It changed how we understand stellar spectra and helped raise astrophysics from basic observations to exact quantitative analysis.

Beyond the Laboratory

Without doubt, Saha’s impact reached way beyond theoretical physics. He created the Institute of Nuclear Physics in Kolkata that left a lasting legacy for scientific research in India. On top of that, his political career as an independent parliamentarian let him promote educational reform and scientific funding strongly. Unlike his peers, Saha strongly believed that industrialization—not village-based development—would push India forward as a self-sufficient nation.

National Visionary

Saha applied scientific principles to real national challenges in remarkable ways. His work on river valley projects came directly from his childhood experiences with flooding. His leadership in calendar reform led to India’s unified national calendar. Through these different projects, he managed to keep his steadfast dedication to merit-based chances and scientific excellence, whatever social barriers existed.

Timeless Inspiration

C.V. Raman might be more widely known, but Saha’s scientific achievements and contributions to institutions have left a permanent mark on Indian science. His life story—rising from a lower-caste shopkeeper’s son to world-renowned physicist—still inspires scientists and citizens alike. Meghnad Saha perfectly combined scientific brilliance with nationalist vision. He ended up proving that determined intellect can surpass all society’s limitations.

Key Takeaways

Meghnad Saha’s remarkable journey from a village shopkeeper’s son to world-renowned physicist offers powerful lessons about overcoming adversity through scientific excellence and unwavering determination.

- Merit transcends social barriers: Despite facing caste discrimination and poverty, Saha proved that intellectual brilliance and perseverance can overcome systemic obstacles.

- The Saha Ionization Equation revolutionized astrophysics: His 1920 mathematical breakthrough transformed stellar spectroscopy from qualitative observation to precise quantitative science.

- Science serves national development: Saha believed large-scale industrialization and scientific research were essential for India’s progress, founding institutions and advocating for educational reform.

- Practical applications matter: He applied scientific principles to solve real problems, from flood control through river valley projects to creating India’s unified national calendar.

- Legacy extends beyond discovery: While never receiving a Nobel Prize, Saha’s contributions to institution-building and scientific education continue shaping Indian science today.

Saha’s story demonstrates that transformative scientific achievement requires not just intellectual genius, but also the courage to challenge social conventions and the vision to apply knowledge for societal benefit.

MK Gandhi, father of the Indian independence movement.

FAQ

What was Meghnad Saha's most famous invention?

Meghnad Saha is best known for developing the Saha ionization equation, which plays a crucial role in astrophysics. This equation helps in understanding the ionization of elements in stars and their relation to temperature. It allows astronomers to determine the physical and chemical conditions of stellar atmospheres, revolutionizing the study of stellar spectra. His work significantly contributed to modern astrophysics by providing a scientific explanation for the classification of stars based on their spectral lines.

What was Meghnad Saha's educational background?

Meghnad Saha was born on October 6, 1893, in Shaoratoli, near Dhaka (now in Bangladesh). He completed his early education at Dhaka Collegiate School and later studied at Dhaka College. He then attended Presidency College in Calcutta, where he was influenced by eminent scientists like Jagadish Chandra Bose and Prafulla Chandra Ray. Saha earned his bachelor’s degree in mathematics in 1913 and completed his master’s in applied mathematics from the University of Calcutta in 1915.

Did Meghnad Saha win a Nobel Prize?

No, Meghnad Saha never won a Nobel Prize, despite being nominated multiple times in 1930, 1937, 1939, 1940, 1951, and 1955. His contributions to astrophysics, particularly the Saha ionization equation, were groundbreaking, but he was never awarded the prize. The reasons remain unclear, but his work continues to be highly respected in the scientific community.

What were Meghnad Saha's major contributions to science?

Apart from his Saha ionization equation, Saha made several important contributions:

- Established the Physics Department at Allahabad University and the Institute of Nuclear Physics in Calcutta (later renamed the Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics).

- Founded the National Academy of Sciences, India, and served as its first president.

- Launched the journal Science and Culture in 1935 to promote scientific discussions in India.

- Played a significant role in Indian politics, getting elected to Parliament in 1952, where he advocated for science and education policies.

What books did Meghnad Saha write?

Meghnad Saha co-authored several books that contributed to the field of physics:

- “A Treatise on Heat” (with B.N. Srivastava) – A fundamental book on thermodynamics and heat, widely used in Indian universities.

- “A Treatise on Modern Physics” – Covers various topics in modern physics, showcasing his deep understanding of the subject.