(February 9, 2026) The new year arrived for high school student Krishiv Thakuria with another feather in his cap. The teenager taught generative artificial intelligence at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Working with Professor Manolis Kellis at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, the 17-year-old helped co-create and instruct courses taken by MIT students and Sloan MBA candidates, many of them senior professionals from global companies such as IMAX, Wix, and Blue Origin. For Krishiv, who is in his final year at The Woodlands Secondary School in Canada, the experience marked a new phase in a journey that has steadily moved from classrooms to research labs, startups, and policy-adjacent civic work.

On social media Krishiv states that he “Co-founded and instructed MIT 6.S189 (Foundations and Frontiers of Generative AI) at MIT EECS with Professor Manolis Kellis,” where he delivered a keynote lecture and mentored students through technical workshops. He also served as “Teaching Assistant for MIT 15.S65 (Deploying AI in the corporation),” teaching MIT Sloan MBA students how to design and deploy AI systems inside organisations.

The youngster was in the news last year after being named a Top 10 finalist for the Chegg.org Global Student Prize 2025, which recognises students who have made a measurable impact on learning and society. By then, he had already built AI-powered education tools used by thousands of students, worked on machine learning systems at one of Canada’s leading AI companies, taught computer science through Stanford University’s Code in Place programme, and led civic technology initiatives aimed at strengthening democratic participation.

Where it began: Teaching students who were left behind

Krishiv’s interest in education technology began at 13, when his middle school teachers asked him to teach a computer science class of around 30 students with learning disabilities. The experience exposed him to a gap he had not fully recognised before. He realised that many students struggle not because they lack ability, but because instruction is not adapted to how they learn.

That early teaching experience shaped his belief that education should be personalised, supportive, and dignified. Rather than seeing AI as a shortcut, he began exploring how it could replicate the kind of one-on-one attention that is often unavailable in classrooms.

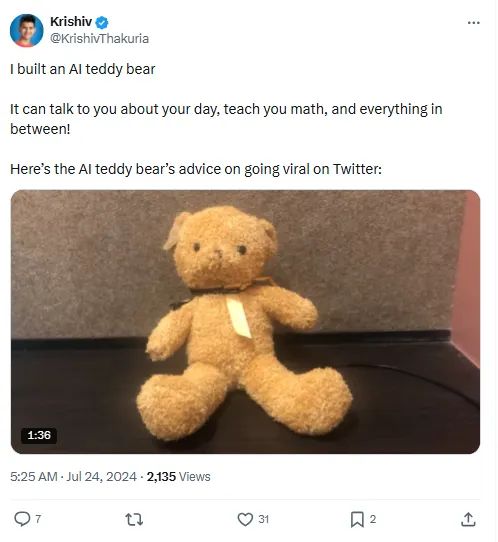

AI powered teddy bears and more

This thinking led to Aceflow, an AI tutoring platform designed for high school students. Aceflow provides personalised explanations and feedback, adapting to individual learning styles. The platform reached thousands of users globally and attracted over $150,000 in funding through programmes such as Microsoft for Startups, Ingenious+, and Emergent Ventures.

Krishiv later extended this idea beyond screens with Charm Bears, which are AI-powered, voice-guided teddy bears created for young students with dyslexia. Designed to be screen-free, the bears use emotionally responsive conversation to help children learn in a way that feels natural rather than clinical. Piloted in Canadian classrooms, the project received backing from IBM for Startups and NVIDIA Inception, with the goal of scaling to classrooms globally.

Learning how AI works in the real world

Alongside building his own products, Krishiv Thakuria sought to understand how AI operates in professional research and industry settings.

At BenchSci, one of Canada’s leading AI companies in pre-clinical research, he worked on machine learning models used in real-world scientific applications. On social media, he describes himself as “their youngest Machine Learning team member,” where he worked on named-entity recognition systems and was mentored by senior AI researchers.

He later worked with Simple Ventures as an AI Engineering Consultant, supporting early-stage founders. As he explains, “I did technical consultancy for portfolio founders, built internal AI tools, and wrote investment memos.” His work included building automated research agents and workflow tools designed to help startups make informed decisions.

Teaching AI at MIT and Stanford

Krishiv’s growing expertise led to collaboration with Professor Manolis Kellis at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL). What began as research involvement soon expanded into teaching and course leadership.

Earlier, he was recruited by Stanford professors Mehran Sahami and Chris Piech to become “the youngest CS instructor for Code in Place,” a global introductory computer science course run by Stanford’s School of Engineering. He taught students across 11 countries, reinforcing his belief that quality instruction should not be limited by geography or institutional access.

Civic tech and responsible AI

Beyond education, Krishiv has applied AI to civic participation. As President of Next Voters, he leads an organisation that, in his words, “deploy[s] responsible AI systems that help voters participate in democracy.” The initiative also runs fellowships to help young people become civic leaders. The organisation’s software has “answered thousands of pressing questions for voters in the US & Canada,” and has received a “$120k/year grant from Google” to expand its reach.

As part of Team DHACK, Krishiv won the top prize for the app Obi along with Damian Matheson, Henry Fu, Alec Ngai, and Cynthia Lam at a hackathon in Canada in 2025

Academic life and what comes next

At The Woodlands Secondary School, Krishiv has served as President of the Peer Tutoring Centre, where he recorded the highest tutoring hours in the school’s history. He is a top gifted student, a former valedictorian, a national speech champion, and a recipient of Canada’s National Book Award that is presented to one student per high school for academic excellence and original thought.

He is also a Villars Fellow at the Villars Institute in Switzerland and has been accepted into programmes such as the Harvard Ventures TECH Fellowship, the Stanford ASES Summit, and received a full scholarship from the Masason Foundation.

As he prepares to graduate this June and consider university programmes that combine engineering with the humanities, Krishiv continues to frame AI not as a threat or a cure-all, but as a tool whose impact depends on how thoughtfully it is taught and applied. His work so far suggests a long-term commitment to using technology not to replace education, but to make it more humane, inclusive, and accessible.