(April 29, 2025) In a world where cultures often collide, one Chinese professor has devoted his life to helping them converse. Professor Wang Zhicheng, a respected academic and passionate Indophile, has quietly emerged as one of the most influential voices promoting Indian philosophical thought in China. Through his translations of ancient scriptures like the Bhagavad Gita and the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, and more than 100 virtual lectures, he has made India’s spiritual heritage accessible, relatable, and deeply relevant to Chinese audiences.

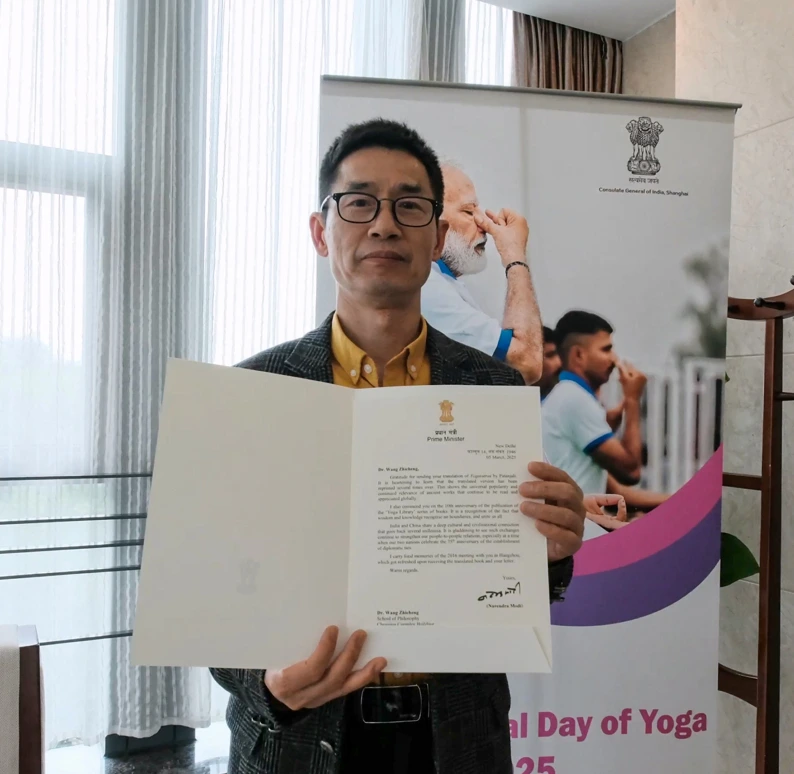

Owing to his 25 published books and long-standing commitment to cross-cultural learning, he recently received a special honour from India. Prime Minister Narendra Modi sent him a personal letter of commendation, which was presented by Consul General Pratik Mathur at a special ceremony held on the prestigious Zhejiang University campus in Hangzhou. In the letter, Prime Minister Modi praised Professor Wang’s efforts in popularizing yoga, Vedanta, and Indian cultural traditions in China.

Professor Zhicheng

This recognition comes at a significant moment, as India and China celebrate the 75th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations this year.

“As a university professor, I have long been dedicated to the study of Indian philosophy and culture, with a particular obsession for yoga, Vedanta philosophy, and Ayurvedic health preservation culture,” Professor Wang Zhicheng tells Global Indian adding “As an intellectual, I am well aware of the great significance of promoting contemporary cultural mutual learning.”

The cultural exchanges between China and India have a long history. The majestic Himalayas have never been a barrier; instead, they have witnessed the dialogue and integration between the two civilizations spanning thousands of years.

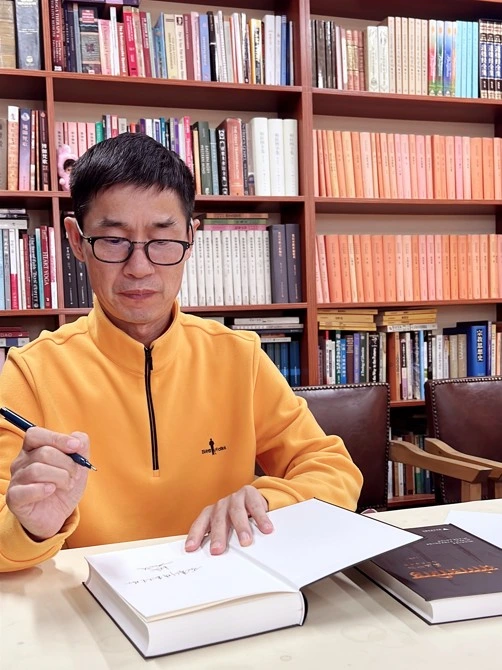

Professor Wang Zhicheng

Meeting Modi

For Professor Wang, the recent honour carried deep personal meaning but it wasn’t the first time he stood in the orbit of India’s leadership. In 2016, during the G20 Summit in Hangzhou, he had the honour of presenting nine books including his Chinese translations of the Bhagavad Gita, Yoga Sutras, Hatha Yoga Pradipika, and Narada Bhakti Sutras to Prime Minister Modi.

Wang vividly remembers the moment. “The meeting was held at the Hilton Hotel by the Xixi Wetland. The shimmering waters and the natural scenery there formed an interesting contrast with the solemn atmosphere of the meeting,” he recalls, “Although our conversation was brief, the few words we exchanged were filled with the expectation for cultural exchanges between China and India.” For Wang, it was a milestone.

Professor Wang Zhicheng with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi

The meeting with Prime Minister Modi was a great affirmation of my years of work.

Professor Wang Zhicheng

A scholar’s journey from Tao to Vedanta

Wang’s interest in Indian philosophy began in his undergraduate years when he came across an English-annotated copy of the Yoga Sutras in his university library. Though the text was difficult to grasp at the time, it planted a seed. Years later, during his doctoral studies, he read a Chinese translation of the Bhagavad Gita. “The ideas from the Bhagavad Gita subtly influenced my academic writing and perspectives,” he notes.

Originally focused on Western religious philosophy, especially John Hick’s theories of religious pluralism, Wang gradually shifted toward Eastern traditions. A pivotal moment came in 2004, when British professor Alan Hunter asked him to translate Swami Vivekananda’s The Road to Yoga. That led him deeper into the yoga tradition, eventually resulting in the translation of Atmabodha by Adi Shankara, which he published under the title Yoga of Wisdom after obtaining the copyright from the Ramakrishna Math in India, and adding his own annotations.

Later, in 2011, a cultural exchange with renowned yoga guru B.K.S. Iyengar at the China–India Yoga Summit inspired him to explore the Sinicization of yoga and the philosophical links between Taoism and Indian traditions like Vedanta. Since then, he has translated key texts and shared his insights through blogs and digital platforms. In 2014, he delivered speeches at conferences in Kolkata and Mumbai marking Swami Vivekananda’s 150th birth anniversary which marked his shift from casual interest to systematic research.

Wang Zhicheng with BKS Iyengar

“By then, my exploration of Indian philosophy and yoga had transformed from passive exposure to active research, evolving from fragmented knowledge to a systematic study,” mentions the professor who has remained committed to the research of yoga philosophy, Vedanta philosophy, and Samkhya philosophy, and have never stopped writing.

Translation as spiritual cultivation

For Professor Wang, translation is more than linguistic conversion. It is a form of inner practice. Reflecting on his time translating the works of Raimondo Panikkar, he recalls the great responsibility it entailed. “He solemnly pointed out that translating his works required a solid foundation in language, philosophy, and theology.”

This principle deeply influenced Wang’s approach to Indian spiritual texts. “Behind the translation work lies the integration of knowledge from multiple fields,” he explains.

For me, bringing texts like the Yoga Sutras or Atmabodha into Chinese was not merely academic. it was a profound practice of spiritual cultivation.

Professor Wang Zhicheng

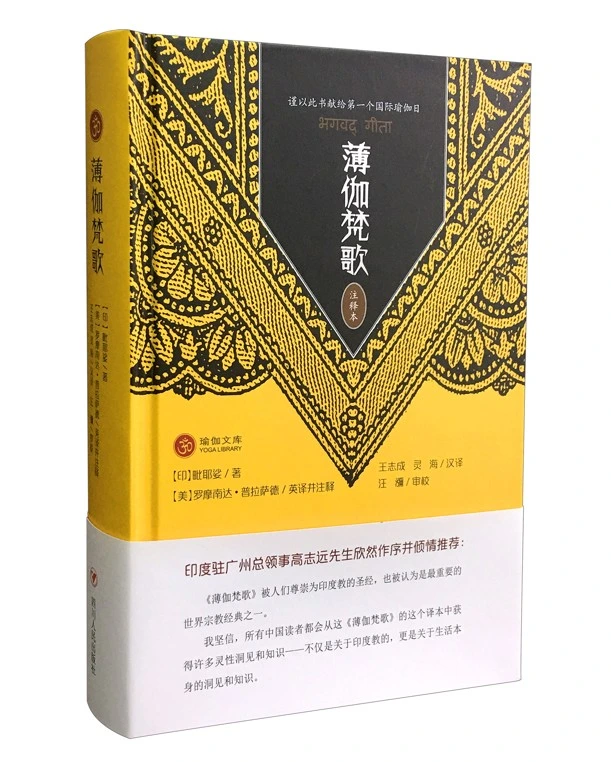

Bringing the Gita to Chinese readers

Wang’s Chinese translation of the Bhagavad Gita, based on the R. Prasad edition, has been printed 17 times since its first release in 2015. “Translating philosophical texts is an in-depth journey that transcends the boundaries of language and thought,” says the Professor.

Bhagwad Gita in Chinese translated by Professor Zhicheng

With help from scholars like Ranjay, a doctoral student from New Delhi, Wang addressed the many linguistic and conceptual challenges involved in rendering Sanskrit ideas into accessible Chinese. One major difficulty was the inconsistency of translated terminology, for example, the word “Krishna” has over five different translations in Chinese. As editor of the Yoga Library series, Wang has worked to standardize this vocabulary. “We adopted a middle path that balances academic rigor and public acceptance.”

Yoga in China

The growth of yoga in China has been rapid and multifaceted. According to Wang, the growth began in the 1980s with internationally recognized yoga teacher Zhang Huilan’s yoga program on television. “This program brought yoga into thousands of households,” he says.

Between 2000 and 2007, yoga expanded into studios. From 2008 onward, an explosion in book publishing and deeper theoretical study followed. Since 2015, yoga has become a mainstream phenomenon across China, embraced not only as a form of fitness but also as a life philosophy.

“More and more people have realized that yoga is a scientific and complete life management model,” Wang explains. His own role in shaping this perception has included books, courses, public lectures, and the curation of China’s leading yoga text series.

Professor Zhicheng

Looking at similarities between India and China

For Professor Wang Zhicheng both China and India are ancient civilizations in the world. Their mighty historical heritages have given birth to splendid cultural systems, and the spiritual resonance between the people of the two countries transcends time and space. Standing at the historical coordinate of the 21st century, he firmly believes that in-depth exchanges of traditional Chinese and Indian cultures, especially in the field of physical and mental cultivation, can not only enhance mutual understanding between the people of the two countries but also carry unique values of the era.

“Such cultural dialogue and inheritance are not only related to the continuous development of the civilizations of the two countries but also serve as an important cornerstone for building a community with a shared future for mankind and promoting world peace and development,” he says.

There are many similarities between Indian yoga and Chinese traditions such as Taoism. They can draw on each other, appreciate each other, and complement each other.

Professor Wang Zhicheng

Vedanta and Taoism in harmony

One of the reasons Indian philosophies has resonated so deeply in China, Wang believes, is its conceptual alignment with Chinese traditions. He sees parallels between Vedanta and Taoist thought, and between the Three Gunas of Samkhya and the Yin-Yang theory.

“Prana in yoga and qi in Taoism share the same essence in different forms,” he says. “These commonalities have allowed yoga to take root in China.”

Indian philosophy’s dual strands, the personal and impersonal interpretations of Brahman, the ultimate reality in Indian philosophy that can be understood either as a personal deity or a formless absolute, also appeal to both intellectuals and the general public. “These two ideological systems coexist without conflict and each has its own followers,” he says.

Professor Wang Zhicheng with Indian Consul General Pratik Mathur

Wisdom through friendship

Throughout his career, Wang has consulted with Indian Swamis, scholars, and doctoral students, everlasting friendships. His 2014 visit to India, for Swami Vivekananda’s 150th birth anniversary, was especially memorable. “Swami Durgananda provided me with meticulous assistance,” Wang says. “Every word of his was like a beacon.”

He returned with a notebook filled with insights. It’s a gift that continues to guide his work today. “These precious pieces of knowledge and insights. are like a continuous source of nourishment,” he mentions.

The power of cultural contrast

While celebrating the similarities between Indian and Chinese traditions, Wang is equally intrigued by their differences. He believes that cultural resonance is not always about alignment. Rather it’s also about contrast and challenge.

“There are many topics in Indian philosophy that are completely different from Chinese culture,” he notes. “The vitality of culture precisely stems from the collision and integration of diverse ideas.”

Yoga Sutra translated by Professor Wang Zhicheng

Wang emphasizes that mutual learning between civilizations thrives in the space between familiarity and difference.

Just as flowing water needs a source to keep it fresh, cultural exchange is the core driving force for the mutual learning of civilizations.

Professor Wang Zhicheng

A cultural bridge between two ancient civilizations

For Professor Wang Zhicheng, his work extends beyond academia into the sphere of cultural exchanges. As a scholar, translator, and advocate of Indian thought, he continues to bridge the spiritual traditions of India and China, striving to create deeper understanding in a divided world. He highlights that yoga’s connection to China began centuries ago through the spread of Buddhism, and today, its modern form is increasingly embraced as a holistic science of life. Quoting Swami Kuvalayananda, he says, “Yoga has a complete message for humanity… for the body, the mind, and the spirit.” In building this bridge, Professor Wang does so word by word, book by book popularizing, Vedanta, and Indian cultural traditions in China.

Professor Wang Zhicheng

Also Read: Gaiea Sanskrit: British by birth, Indian by soul

Also Read: Viral Doshi: Two decades of Ivy League mentorship, and now a calming force in the Harvard storm