(May 13, 2025) When news broke in February 2025 of Ken Zuckerman’s passing at the age of 72, the Indian classical music fraternity mourned not merely the death of a sarod player, but the departure of one of its most beloved insiders. A man born to Russian-Jewish parents in America, Zuckerman’s legacy resonated far beyond nationalities, genres, or borders. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s words to him while he was alive encapsulates how the American soloist made classical Indian music his identity and helped increase its reach abroad, “Your dedication to Indian classical music and efforts for its spread, a highlight of India’s vibrant cultural diversity, is highly appreciable. May your ‘Sarod’ keep on serving music lovers all across the world,” the PM had once remarked.

Zuckerman died a decorated artist. In December 2023, he received the “Lifetime Achievement Award” from the Sangeetanjaly Foundation in Hyderabad. His Grammy-nominated albums Diaspora Sefardi and Indian Ragas & Medieval Song remain strong examples of his boundary-blurring artistry. But beyond accolades, what made Ken extraordinary was how he became part of India’s sonic and spiritual landscape. Clad in a humble kurta-pyjama, speaking softly but passionately, Zuckerman wasn’t just playing the sarod, he was living it.

A winding path to music

Ken Zuckerman’s childhood was far removed from the resonant strains of Indian classical music. Growing up in Basel, Switzerland, after moving from America, his dreams were more in tune with baseball than Bhairavi. Music was a hobby. He sang, tinkered with the piano, and strummed the guitar until his twenties. “I played the electric guitar, rock’n’roll, acoustic guitar, and did a lot of composing in jazz and folk,” he recalled in an interview.

Music wasn’t absent from the family home, but it was casual. Zuckerman loved telling the story of his father’s musical philosophy. “I play the tape-recorder,” his dad would joke.

But destiny had other plans. At 20, while studying in Iowa, Ken stumbled into an Indian classical concert featuring Ustad Ali Akbar Khan and Pandit Shankar Ghosh. Bored one evening and uninterested in any movie screenings, he walked into a performance that would change his life. “Little did I know,” he would later reflect, “that by doing so, I was about to change my life’s destiny.”

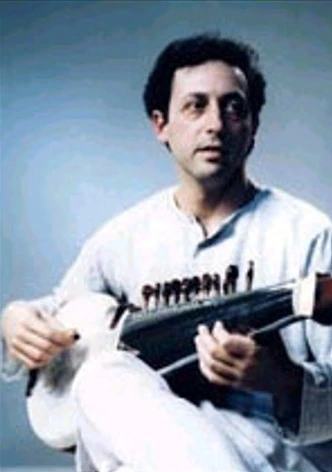

Ken Zuckerman during his younger days

Discipleship with a legend

After the concert, Zuckerman learned of the Ali Akbar College of Music in California. He visited during spring break and immediately enrolled in a six-week summer course. What began as curiosity transformed into discipleship. Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, son of the legendary Baba Allauddin Khan accepted him as a student. Zuckerman began with the sitar, but the sound of the sarod delighted him more.

His switch to the sarod wasn’t merely musical. It was spiritual. “I had a dream,” he said, “in which Ustad Khan handed me a sarod.” The very next day, he made the change. And so began 37 years of learning under the maestro.

Khan never gave praise easily, yet in Zuckerman, he saw immense promise. In his eighth year at the college, Zuckerman was chosen for the ‘gandabandh’ ceremony, where the guru ties a sacred thread on the student’s wrist marking formal initiation and a deeper relationship.

“I am so lucky that my first contact in Indian classical music was with Ustad Ali Akbar Khan. Who could I have asked for a better teacher?” he said. Even after Khan’s death, Zuckerman continued learning from recordings, practicing daily with reverence.

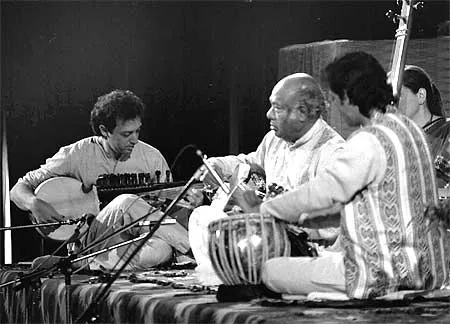

Ken Zuckerman with his Ustad

An American in kurta-pyjama, embracing Indian aesthetics

Zuckerman never sought to “Indianize” himself in a gimmicky way, but he internalized Indian values and aesthetic subtleties deeply. Dressed often in simple kurta-pyjama, he embodied the calm, patient temperament so revered in classical circles. “The average Indian’s outlook on life,” he once said, “is patient, philosophical, accommodative and full of tolerance.”

For Zuckerman, Indian music wasn’t just a sonic art. It was a lifestyle.

Music encourages one to go into the world of vibrations where it doesn’t matter whether you are saying a Hindu chant or a Muslim prayer. It is a stage beyond that, a spiritual experience.

Ken Zuckerman

The uphill road to acceptance

Zuckerman’s path to recognition wasn’t smooth. “Until five-six years ago,” he said in 1992, “I was up against a brick wall back home despite studying for 15 years and receiving good notices here.”

Many in Europe and America viewed Indian music as something sacred, untouchable by outsiders. “Westerners who understand Indian music can see I have learnt it the proper way,” he explained. “Those who hear me with reservation think Indian music must be performed by an Indian.”

To gain authenticity, Zakir Hussain and Swapan Chaudhuri advised him to establish credibility in India first. And he did. Performing alongside his guru and with maestros like Zakir, Zuckerman slowly convinced skeptics. “If Khansahib, Zakir or Swapan were performing with me, impresarios began to believe I must have some standing.”

Basel, a new home for the sarod

In 1985, Ustad Khan founded the Ali Akbar College of Music in Basel and entrusted Zuckerman with running it. The non-profit thrives on support from European and American patrons and remains rooted in Khan’s original Californian curriculum. Zuckerman, who also taught at the Basel Music Academy, brought the sarod to a European audience with authenticity and grace.

His teaching method mirrored that of his guru. “The methodology of teaching was very direct,” he explained. “Khansahib led the class in singing and we were encouraged to follow first in singing and later repeat the tune on the same lines with our instruments.”

He understood the challenges Western students faced in abandoning notated music and learning by ear. “It is an education in itself,” he often said, emphasizing how Indian music demands an entirely different kind of listening.

The aesthetics of restraint

In an era where speed and virtuosity dominate classical performance, Zuckerman stood apart. “I have a tendency to go for the lyrical approach,” he explained. “The mood of a raga is the essence in Indian music. If the fundamental melodic line is sketchy, mere tayyari or striving for speed will not give the desired effect.”

In Calcutta, some young sarod players laughed at him for not playing fast. “Having learnt outside India,” he mused, “I am lucky I have been out of this vicious circle.” He wasn’t trying to impress; he was trying to express.

Ken Zuckerman

Guru-shishya, on and off stage

One of Zuckerman’s greatest honours was performing with his guru. “I regard performing with him an extension of my learning process to a higher plane,” he said. Playing alongside Ustad Khan wasn’t just about sharing a stage, it was a continuation of the classroom, elevated to the public eye.

Of Khan’s original compositions like Chandranandan and Gauri Manjari, Zuckerman was deeply appreciative. “Chandranandan is his very own special raga. It’s an artistic achievement, a Kunst Werk as we say in German.”

He even experimented with jugalbandis, notably performing alongside fellow American sitarist James Pomerantz. Yet, Zuckerman always gravitated more toward the intimate dialogue between sarod and tabla.

A taste for India, beyond music

Zuckerman’s embrace of India was never limited to ragas and rhythms. It extended to the everyday, the tangible, the flavoursome. He once chuckled in an interview about how easily he took to Indian food. “I love the food,” he said with the enthusiasm of a man who had learned to not only play the sarod but also relish dal, sabzi, and biryani. This love wasn’t performative, it was heartfelt. Whether enjoying a quiet meal after a concert or grabbing a plate at a roadside dhaba during his India tours, he found joy in India’s culinary richness.

His fondness for Indian cuisine became symbolic of a broader cultural affection. He never saw India as ‘foreign’, rather as home. “One thing that attracted me to my ustab Khansahib,” he reflected, “was the way he is, the way he speaks, his outlook on life. It’s all in harmony.” That harmony, for Ken, included music, spirituality, and yes, food too.

Ken Zuckerman

A life of teaching and learning

Zuckerman was as much a teacher as he was a performer. At the Basel academy, he held lectures, workshops, and public-school demonstrations. Some students came for an introduction, others for immersion. “Those listening regularly can now keep tala during a recital,” he said with quiet pride.

Yet, he was realistic about the odds. “Few are foolhardy enough like me to give up everything else and go for it without any assurance about the future,” he laughed.

Ken Zuckerman’s passing in early 2025 marked the end of a remarkable journey, one that began in America, matured in India, and flowered across continents. His story is a reminder of music’s power to traverse borders and beliefs. He didn’t just play the sarod. He became one with it. In a world often divided by nationality and identity, Ken Zuckerman embodied a rare synthesis of East and West, disciple and master, outsider and insider.

A journalist once described him after an interview, “this gentle American is a fitting cultural emissary to conquer the world with his music, an alien here to bring home the innate sweetness of the sarod with his utterly disarming Indianness.” In those few words lay the essence of the sarod player whose music carried both the soul of India and the warmth of humanity.

ALSO READ: Ukraine’s Vijaya Bai: How Viktoria Burenkova promotes Bharatanatyam in Kyiv