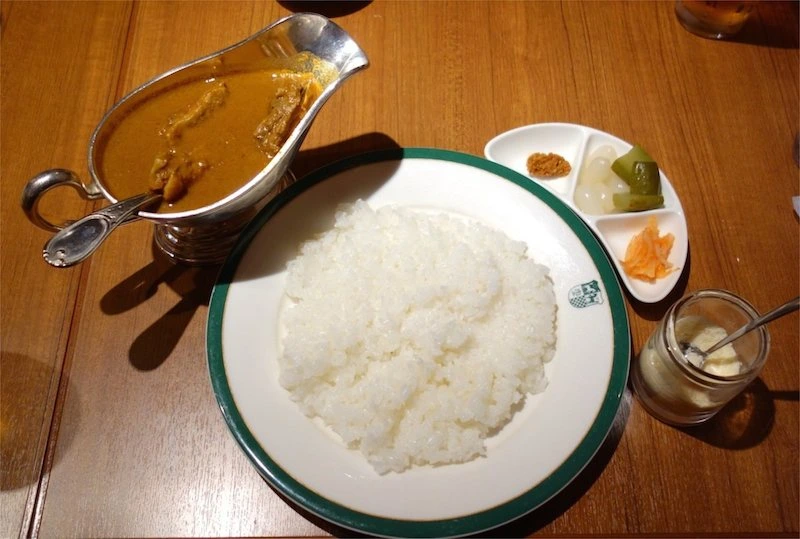

(Jun 22, 2025) In the heart of Shinjuku,Tokyo’s business and entertainment hub, the scent of slow-simmered spices, caramelized onions, and ghee rises steadily from the kitchen of Nakamuraya, a restaurant that has been a fixture of the neighborhood since 1909. Throughout the day, patrons arrive from across the city. They are local office workers, curious tourists, and devoted regulars. One of the most popular dishes of the restaurant is Indo-Karii, a soulful chicken curry that blends Indian spice with Japanese subtlety. Yet for many, the attraction is more than just the dish, it is the story behind it. The story begins not in a Michelin kitchen, but in a basement of a bakery sheltering a fugitive Indian revolutionary. His name was Rash Behari Bose.

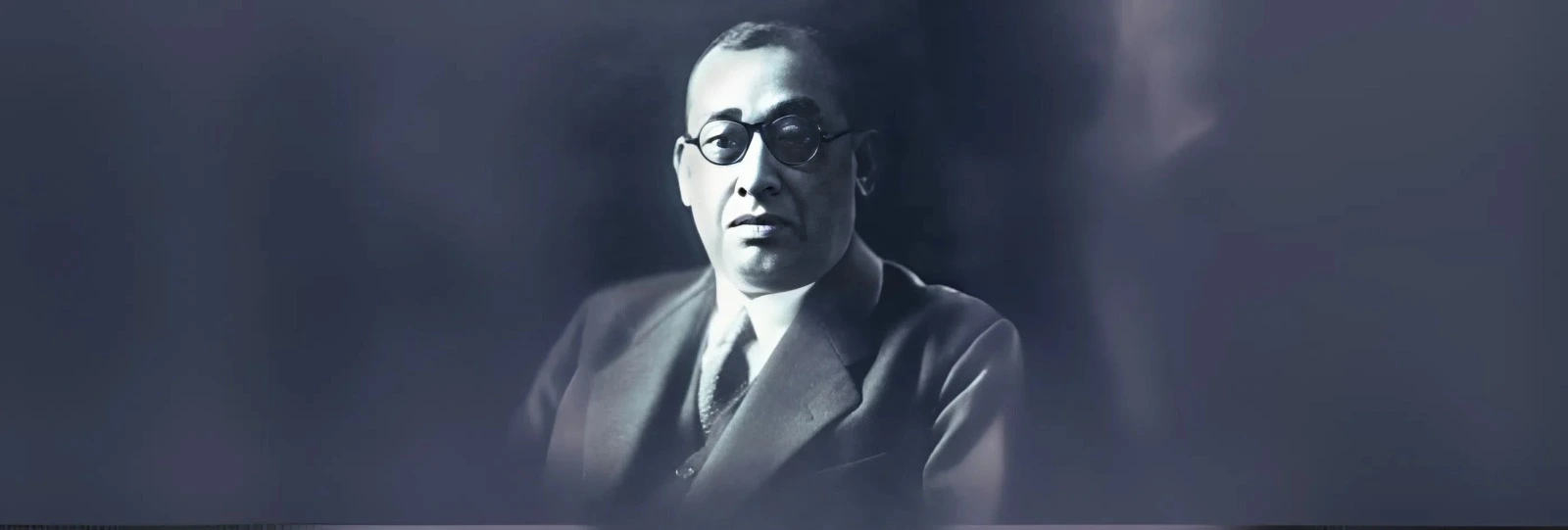

Rash Behari Bose

Fleeing British surveillance, the Indian revolutionary arrived in Japan in 1915 and was sheltered by the Soma family, proprietors of the then-modest Nakamuraya bakery. He eventually married their daughter, Toshiko Soma, and in a quiet act of cultural and culinary diplomacy, began crafting a dish that brought together Indian warmth with Japanese refinement.

The result was Indo-kaari, a spicier, more aromatic curry made with ghee, garam masala, and slow-cooked chicken. At a time when Japanese palates were accustomed to local and British-style food, Indo-kaari stood apart with its depth and authenticity. The dish became a sensation, and remarkably, it is still served today at Nakamuraya’s more than 100-year-old flagship restaurant, which has grown into a landmark in Japanese culinary history.

In 2015, the restaurant was transformed into a 100-seat heritage eatery, adorned with sepia-toned portraits of Bose and the Soma family. Beneath those quiet gazes, guests unknowingly partake in a living archive of resistance, cultural exchange, and affection. What reaches their table is not just a meal, it is an edible memoir, born of exile, tempered by love, and seasoned with history.

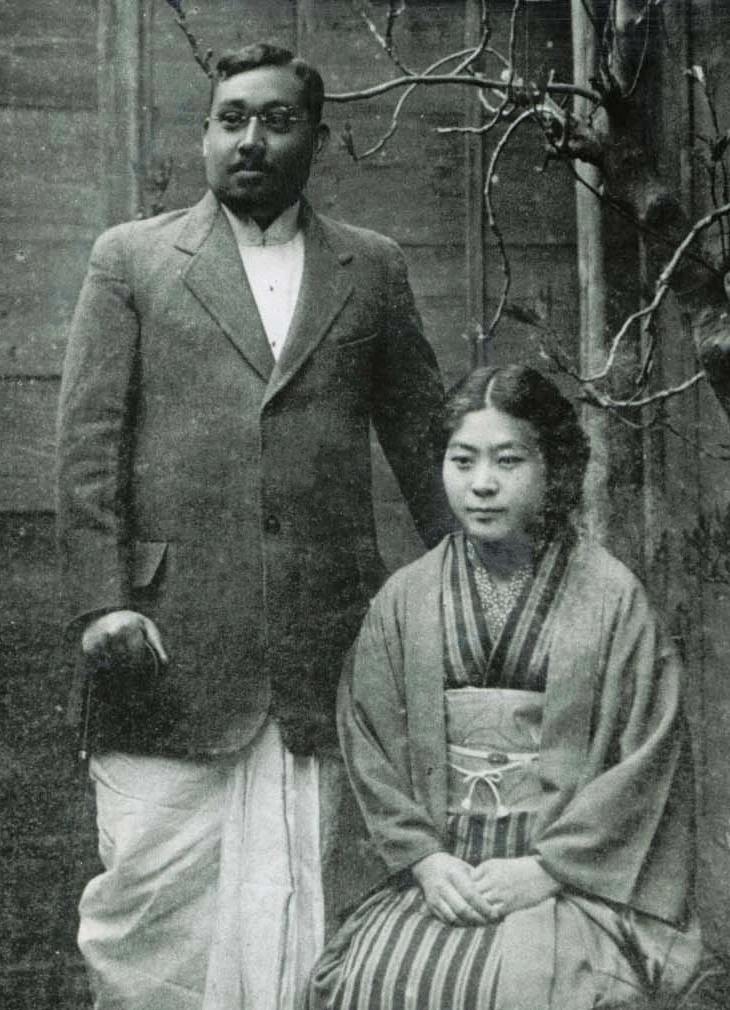

Rash Behari Bose and his wife Toshiko Soma

Bombs, bounties, and a fateful escape

Born in 1886 in Bengal, Rash Behari Bose was deeply shaken by the Partition of Bengal in 1905. He resigned from his government job to become part of India’s underground resistance, aiming to upend British rule. In 1912, he masterminded the audacious assassination attempt on Lord Hardinge, then Viceroy of India, during a procession in Delhi. Though the Viceroy survived, Bose became a hunted man, facing a death sentence.

With colonial agents on his tail, Bose fled India in 1915 and took refuge in Japan, arriving just as the island nation was emerging as an Asian power with anti-colonial sympathies.

The Tokyo hideout: Basement of resistance

For several years, Bose remained underground in Tokyo. British pressure mounted on Japan to extradite him, but he found refuge in the Nakamuraya bakery, tucked away in a narrow, bustling lane in Shinjuku. The bakery was owned by Aizo and Kotsuko Soma, prominent Japanese intellectuals and philanthropists who supported India’s struggle for freedom.

The Nakamuraya bakery on Shinjuku’s central shopping street in the early 20th Century | Photo Credit: Nakamuraya

The Somas sheltered Bose in their basement, shielding him from British agents. In that haven of political hope and warm bread, Bose forged a deep bond with the family, especially their daughter, Toshiko Soma, a talented painter with a quiet revolutionary spirit of her own.

Love, loss, and a curry is born

In 1918, Rash Behari married Toshiko. It was an act considered socially radical in Japan at the time. Their interracial union made headlines and invited criticism, but it also became a powerful symbol of cross-cultural solidarity. It was during these years of exile and love that Bose shared his favourite chicken curry recipe with the Somas, blending Bengali spices with Japanese techniques.

The Soma family adored it. Slowly, the dish made its way from the private table to the public palate.

Tragically, Toshiko died of tuberculosis in 1925 at just 28, leaving behind two children and a heartbroken Bose. But from this personal loss emerged a public mission.

Bose with his wife, children, parents-in-laws and Rabindranath Tagore during the latter’s Japan visit

From kitchen to cultural phenomenon

In 1927, Bose helped transform the Nakamuraya bakery into a restaurant, launching a modest curry counter on the upper floor. He personally selected spices, supervised the cooking, and brought authenticity to every serving. The dish, dubbed Indo-Karii, was unlike the bland, roux-thickened Japanese curries of the time. This was real curry, which was aromatic, spiced, and soulful.

Passersby were drawn in by its aroma. Print media dubbed it as ‘Taste of Love and Revolution’, fusing the story of Bose’s resistance and romance into the curry’s branding. Its success was meteoric. Eventually it grew into a public craze.

Nakamuraya itself grew into a culinary empire. It became one of Japan’s oldest and successful food brands, eventually going public on the stock exchange. In 2015, the original restaurant was renovated into Nakamuraya Manna, a 100-seat heritage eatery by the great grandsons of the Bose-Soma family. Guests dine under vintage photos of the Somas and Bose, surrounded by whispers of a century-old revolution.

Shinjuku Nakamuraya Manna Restaurant after renovation

Revolution over curry: The INA connection

Even while transforming Japan’s palate, Bose never forgot India’s freedom struggle. In the 1930s and ’40s, he laid the groundwork for what would become the Indian Independence League, which later evolved into Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s Azad Hind Fauj (Indian National Army). He contributed political essays to contemporary Japanese publications, building sympathy for colonized India.

Nakamuraya’s back rooms doubled as planning chambers, where curry and politics were served side by side. Even in illness, his devotion endured. In 1944, lying in a hospital bed, when asked what he craved most, he replied:

“How can I have an appetite when the nurses don’t allow me to have the food I most desire?” That food, of course, was Nakamuraya’s Indo-Karii.

Indo Karii

Honouring an unsung hero

Rash Behari Bose died in 1945, just months before India’s independence. Though he is remembered in Japan for his culinary gift, in India his revolutionary legacy remained underappreciated.

That began to change in 1967, when the Posts and Telegraphs Department of India issued a commemorative postage stamp in his honour. In Kolkata, his memory lives on in Rash Behari Avenue, a bustling arterial road that reminds the city of one of its bravest sons.

Bose’s story is a reminder that not all battles are fought in the open. Some, like Bose’s, are simmered slowly, seasoned with patience, purpose, and quiet fire.

ALSO READ: Abhishek ‘Lucky’ Gupta: Seoul’s most beloved Indian bridging cultures between India and Korea