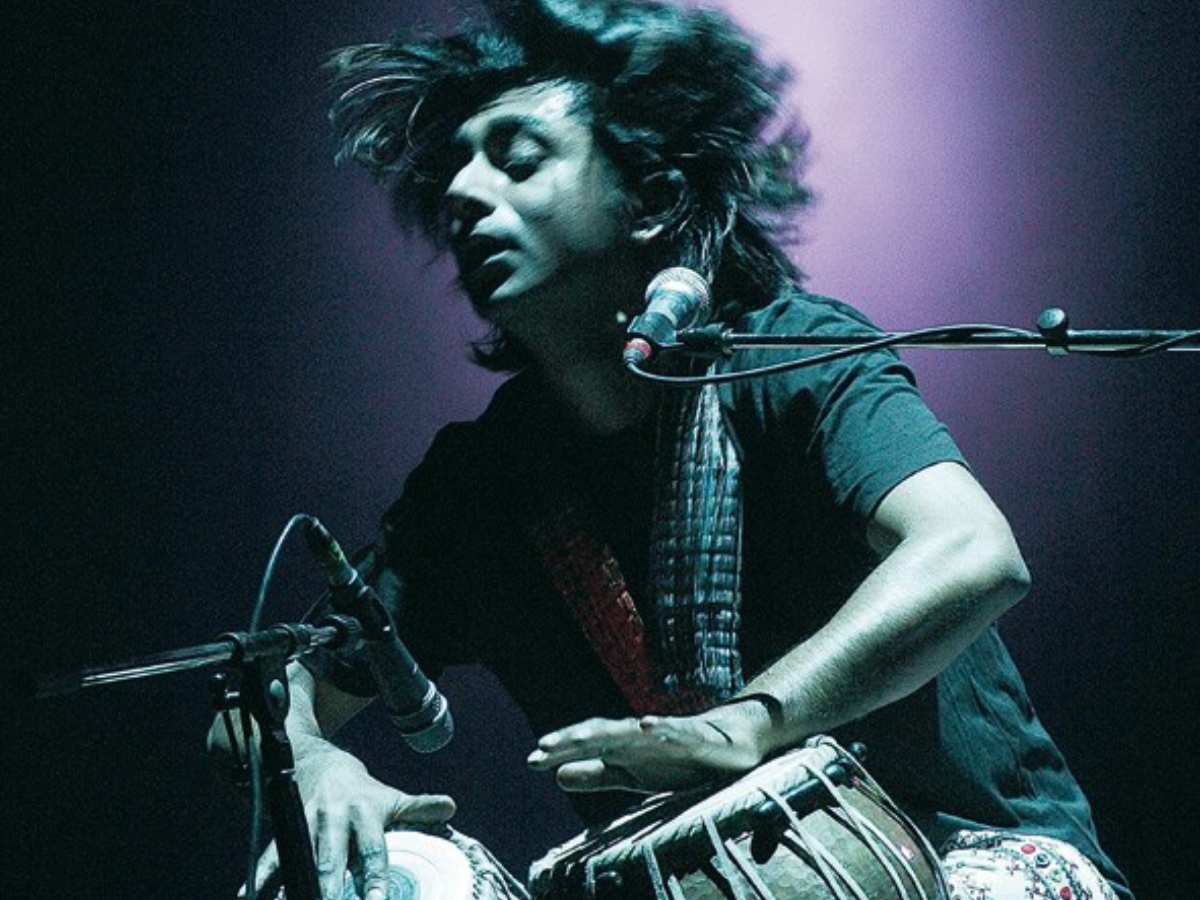

(May 27, 2025) On a cold night in London in the late 1990s, a group of young British Asians gathered inside an old warehouse near Brick Lane. The room was dimly lit, filled with the heavy beats of drum and bass. But this wasn’t your usual club night. In the middle of the stage sat a man playing the tabla — his fingers moving quickly, mixing traditional Indian beats with modern electronic music. The man was Talvin Singh, a London-born musician of Indian descent, trained in classical Indian music. He had performed with global stars like Björk and Madonna, but he was best known for something else entirely: creating a sound that brought together the East and West in a way that felt entirely new.

That night, he wasn’t just performing. He was giving a generation of British Indians something they had rarely experienced before: a sound that felt like home.

Talvin Singh

It would come to be known as the Asian Underground — a movement that began in clubs and bedrooms, but echoed through the identity of a generation.

A Generation in Between

To understand what the Asian Underground meant to British Indians, we need to start with what came before it.

From the 1950s through the 70s, thousands of Indian families arrived in the UK. Some came from Gujarat and Punjab. Others had lived in East Africa and were forced to leave during political upheaval. Many settled in working-class neighbourhoods like London, Birmingham, and Manchester, building new lives under the shadow of post-colonial Britain.

Their children were born and raised in Britain. But they often felt stuck between two worlds. At home, they were expected to follow Indian traditions — eat desi food, speak their mother tongue, and listen to classical music. Outside, they were surrounded by British pop culture. They loved Oasis and Madonna but also knew the lyrics to old Bollywood songs. They didn’t feel fully Indian or fully British. They were something in-between.

Music gave them a way to express that feeling.

The Sound of Two Worlds Colliding

By the 1990s, some British-Asian musicians started creating their own sound. They didn’t want to choose between their Indian heritage and their British upbringing — so they combined them. The result was the Asian Underground.

In east London, Talvin Singh’s Anokha club nights at the Blue Note became a space for young British Indians who felt caught between cultures. Singh, a skilled tabla player trained in Indian classical music, wasn’t focused on tradition alone. He wanted to experiment — to blend the sounds he grew up with and the city he lived in.

And that city was London — loud, fast, and full of energy.

At Anokha, Singh mixed jungle, drum and bass, ambient music, and the ragas he had grown up with. The result was something completely new in British music — a sound that didn’t try to explain itself. It just existed.

“I wanted to break rules,” Singh later told The Guardian. “It was a beautiful experience.”

Outcaste and the West London wave

Across the city, another voice was emerging. Shabs Jobanputra, whose Indian family had fled Uganda’s regime in the 1970s, launched Outcaste Records. What started as a club night soon became a label that amplified a new wave of British Indian voices.

Artist Nitin Sawhney

Artists like Nitin Sawhney brought jazz, flamenco, and Carnatic music into dialogue. His 1999 album Beyond Skin — nominated for the Mercury Prize — included samples of his parents reflecting on migration and memory.

“The whole idea was that British Indians could feel they have a relevance and identity within the wider culture,” Sawhney said. “That’s what was exciting.”

Music as mirror

What made the Asian Underground special was how clearly it spoke to the inner lives of British Indians. These weren’t typical pop songs. They were layered, thoughtful, and sometimes challenging. They captured what it felt like to be both British and Indian at the same time.

Composer Shammi Pithia, who grew up in east London, remembered hearing the music live for the first time. “There was a sense that this music was for us and by us,” he said. “And that was very powerful.”

The music didn’t try to smooth over identity — it showed the mix of cultures as it really was. Singh’s OK went on to win the Mercury Prize. Sawhney’s Beyond Skin became a key album for its emotional, blended style. But more than the awards, their real impact was helping British Indian youth feel understood.

From silence to statement

The movement didn’t appear overnight. It came after years of being overlooked. For a long time, British Indian identity was either ignored or shown in a shallow way in mainstream British culture. Music became one of the few ways to tell a different story.

“Listening to Beyond Skin was revolutionary,” said Pithia. “It made me realise that Indian music isn’t just for Indian people. It made me proud to be a British Indian musician.”

This pride was quiet, even careful — but it was important. It marked a move away from trying to blend in, toward creating something new and true to who they were.

The Fade — and the Legacy

By the early 2000s, the scene began to fade. Some artists signed with big labels, others moved on to different projects. Newer music trends took over. But the influence of the Asian Underground never fully disappeared.

It opened the door for artists like M.I.A., Riz Ahmed, and even some grime musicians to mix South Asian sounds with global beats. It also made it easier for second- and third-generation South Asians to talk about identity in new ways.

Today, a new wave of young artists and DJs — from collectives like Daytimers and No Nazar — are picking up where the Asian Underground left off. They’re blending old Bollywood tracks with house music, making queer desi club nights, and using music to say, “We are here, and we belong.”

More Than Music

The Asian Underground was never just about beats or instruments. It was about claiming space — a way of saying that being both British and South Asian didn’t have to be confusing. It could be powerful.

For a generation of British Asians, this music became a mirror. They didn’t fully belong in British culture, and they didn’t feel completely rooted in the countries their parents came from. The Asian Underground helped them make sense of that in-between space. It gave them something that felt like their own — a sound that blended heritage with the world they grew up in.

It wasn’t just music. It was identity. It was creativity, strength, and pride. And in dark London warehouses, with tabla rhythms bouncing off concrete walls, a generation danced — not just to a beat, but to the sound of who they really were.

Also Read: Punjabi-Reggae Revolution: How a search for identity led to the birth of ‘British Bhangra’

Also Read: Band, Baaja, Baraat: Wall Street to FDR – big fat Indian weddings take over New York streets

Also Read: Paris in Sync: How Balakumar Paramalingam is bringing Carnatic rhythm to Europe