(July 1, 2025) Amar Bose, a Bengali-American inventor, MIT professor, and founder of Bose Corporation fused intuition, Eastern philosophy, and relentless experimentation to transform the way the world experiences sound.

Bose’s legacy echoes every time a compact speaker fills a room with rich acoustics, when a toddler naps soundly on a noise-cancelling flight, or when a driver glides through traffic accompanied by cello concertos at near-whisper levels. These modern auditory comforts trace back to a man who, as a cash-strapped MIT freshman, could afford just “two hours a week” of classical vinyl, but whose obsession with sound led him to reimagine how deeply music could move the human spirit. In 1964, he established Bose Corporation, an American audio equipment company known for its premium speakers, headphones, and sound systems used in homes, cars, and aviation.

From basement radios to the gates of MIT

Long before the Bose logo graced living-room speakers and airplane headsets, Amar Gopal Bose was just a teenager fixing broken radios in the damp basement of his family’s Philadelphia home. The basement workshop was more necessity than hobby; World War II had choked the family’s Indian doormat-import business, and the extra income kept the household afloat. But it also revealed something deeper, a fascination with how things worked and, more importantly, how they could work better.

That restless curiosity carried Bose on a scholarship to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1947. He arrived, by his own admission, “outclassed” in calculus but armed with radar tubes, an oil-burner transformer, and the memory of building his neighborhood’s first television. Over nine years at MIT he clawed through undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral work, capping his PhD with a reward he thought he had earned: a “first-class” hi-fi stereo system.

Instead, disappointment struck the moment music filled his dorm room. The lavishly specified speakers sounded lifeless. Why did the numbers on paper promise brilliance while his ears reported boredom? That single question would seed a lifetime of research in acoustics and, more radical still; psychoacoustics, the study of how the human brain experiences sound.

Ignoring the rulebook

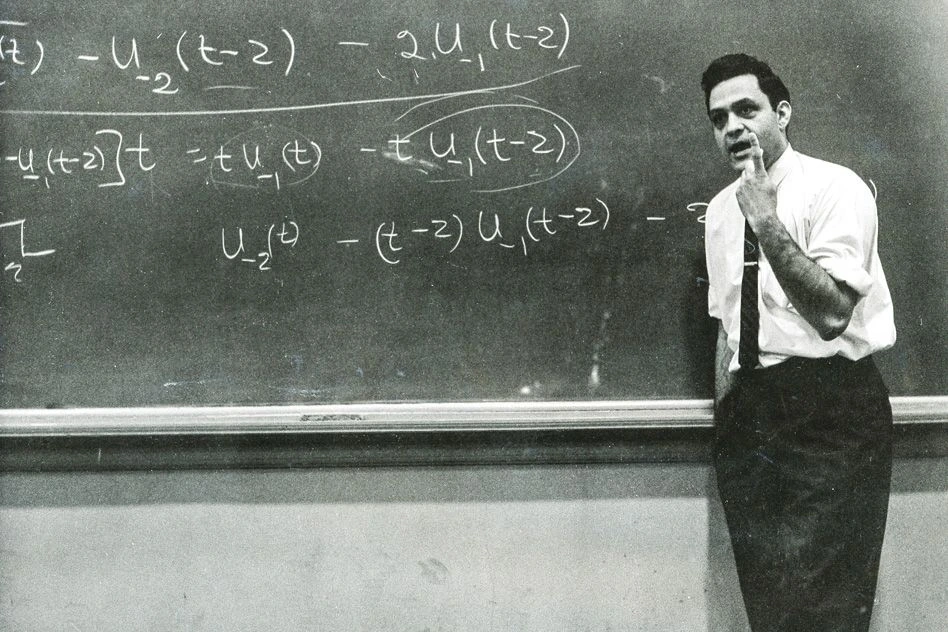

By 1964 Bose was teaching MIT’s intimidating network-theory course, ripping up the old syllabus and turning recitations into Socratic explorations. “I wanted to teach thought, not formulas,” he later said. Yet the bigger gamble came outside the classroom when mentor Professor Y. W. Lee urged him to commercialize his ideas rather than let them “pass through (his) fingers.” All he needed was a name.

“We were trying out various combinations with ‘acoustics’ and ‘electronics’ but couldn’t register any of them,” Bose recalled. Lee’s advice was pragmatic: pick something short, pronounceable, and open-ended. In the next filing round, “Bose” sailed through the U.S. Patent Office. It was accidental modesty, but the four-letter marque would soon rank with Sony and Philips in consumer recognition.

From day one the company’s charter was unusual: stay private, reinvest every dollar into R&D, and protect engineers from Wall Street’s ninety-day judgment cycle. “We’re very clear that balance sheets will not be used to fire presidents,” Bose insisted. “I would have been fired four or five times if this were a public company.”

Turning rooms into concert halls

Bose’s first commercial loudspeaker, the 2201 flopped. Conventional reviewers bristled at its corner placement and active equalizer, ideas then deemed heretical. But the early failure emboldened him. In 1968 he unveiled the Bose 901 Direct/Reflecting® system, a nine-driver box that bounced 89 percent of its output off the walls, delivering only 11 percent directly to the listener. The design mimicked the ratio of direct to reflected sound in Boston’s Symphony Hall, turning suburban living rooms into mini concert venues.

Audiophiles were stunned; some were scandalized. Specifications looked ordinary with no bone-rattling bass, no diamond-dusted tweeters, yet the experience felt uncannily live. The revelation wasn’t in the parts but in the perception. Bose had proved that how we hear matters more than what the lab microphone measures. This psychoacoustic leap would guide every future product bearing his name.

Ideas that don’t come from rational thought

The 901 success could have made Amar Bose a comfortable audio executive. Instead, he doubled down on risk and intuition, crediting his Indian heritage for the outlook. “An important lesson I’ve learnt from my Indian background is that the fall-out of research is not always tangible,” he said. While Western engineering “has put technology education in a tunnel,” Eastern philosophy “gives a broader view and a willingness to believe that a lot of things are possible.”

He told a Ramakrishna Mission monk in 1956 that many of his patents arrived not by analysis but by “flash of inspiration.” From that epiphany he distilled a personal philosophy that “Inventions don’t actually come from rational thought; it’s the wow factor that’s most important.”

Nowhere was that credo clearer than on a turbulent flight from Zurich in 1978. Annoyed by engine roar, Bose imagined a headset that could erase it. By touchdown he had sketched the core equations for active noise cancellation. The first Bose Aviation Headset reached cockpit pilots in 1989, a full decade before consumer QuietComfort™ models became airport staples. The technology was less about silence than sanity, about arriving after an overnight hop with hearing and temper of travellers intact.

The privilege and price of staying private

Keeping Bose Corporation private was not a romantic whim; it was a strategy to decouple invention from quarter-to-quarter profits. “One of the best decisions I ever made was keeping the company privately held, so we can take short-term pain for long-term gain,” Bose said.

His critics argued that secrecy cloaked failures, but inside the company the freedom meant pursuing “tens of millions of dollars” in projects that, for years, produced nothing but insight. When an especially expensive moon-shot devoured budgets in the 1990s, Bose wagered his own salary alongside the engineers’. He saw it as moral insurance: if Wall Street could not fire him, he could not in good conscience fire them for betting on the future.

In 2011 he pushed the principle further, donating the company’s non-voting shares to MIT. Dividends would sustain the Institute’s research while preserving Bose’s private status. It was an extraordinary philanthropic move where innovation funded innovation, indefinitely.

Mentoring minds at MIT

Although business blossomed, Bose never abandoned the chalkboard. He taught at MIT for 45 years, turning a dry prerequisites course into a cult favourite across departments. Students called it “Life 101” because homework wasn’t just problem sets; it was thinking in public. Exams were open-book, time-unlimited, terrifying and liberating.

William R. Brody, now president of Johns Hopkins University, still recalls the hush before a Bose lecture: “You could hear a pin drop. His class gave me the courage to tackle high-risk problems.” That courage echoes in today’s startups where many founders once copied network equations under Bose’s blackboards.

An engineer’s philosopher

In conversation Bose toggled between quantum physics, cold fusion, and Sanskrit texts with equal gusto. He practiced daily eye exercises, insisted on perfect night vision at seventy-five, and could drift a rental Cadillac along Hawaiian cliff roads faster than logic allowed. Friends joked that radar detectors merely confirmed what intuition told him moments earlier.

Yet behind the maverick persona stood a rigorous scientist. Each intuitive flash was followed by months or even years of brutal validation. If data disagreed, he recalibrated the hypothesis without mercy. That blend of creative license and empirical discipline is perhaps his real bequest to engineering: the permission to dream and the obligation to test.

The soundtrack lives on

Amar Bose died on July 12, 2013, at age eighty-three, but the culture he built keeps humming. Today Bose Corporation’s lineup spans smart speakers, Auto-EQ earbuds, and advanced automotive sound fields that map individual seating positions. The psychoacoustic mindset that products must satisfy the listener, not the oscilloscope, remains the north star.

Meanwhile, MIT alumni carry his methods into sectors as diverse as biomedicine and climate tech. They recite his maxim that “good research doesn’t come out of” five-year CEO tenures chasing stock bumps. They remember a professor who abolished time limits and a CEO who canceled accounting meetings to chase a better windshield wiper.