(August 19, 2025) For those who left India’s shores — by ship in the 19th century or by plane in the decades that followed — photographs were often the only way to hold on to what was left behind. Faded portraits tucked into suitcases, studio shots mailed across oceans, sepia family albums that travelled from one generation to the next — they carried more than faces; they carried belonging.

On World Photography Day, it’s worth remembering how the camera has been both witness and companion to the Indian diaspora. For indentured workers in the Caribbean and East Africa, photographs were proof of arrival — carefully posed studio shots against painted backdrops that suggested dignity in foreign lands. For later migrants to the UK, North America, and the Gulf, photographs became letters of love — weddings captured on film, babies in their first homes abroad, moments that stitched families across continents.

Deoki Family in Suva | Photo Courtesy: Deoki Family History Page/Facebook

And for many Indian-origin photographers, the camera has become more than a tool of memory. It is a way to ask questions of identity: who am I, what is home, how do I belong? From Sunil Gupta in London to Miraj Patel in New York, from the portraits of N. V. Parekh in Mombasa to the contemporary work of Gauri Gill, photography has not only preserved the diaspora’s past — it has shaped how it sees itself in the present.

What Photographs meant for the diaspora

For the indentured Indians sent to the Caribbean, Mauritius, and Fiji in the 19th century, photographs were often the only link to a homeland they might never see again. A single studio portrait — a neatly draped sari, a carefully combed moustache — could cross the kala pani as proof of survival, assuring families in Bihar or Uttar Pradesh that their loved one still stood strong in a faraway land. In the cane fields of Trinidad or the barracks of Suriname, photographs became treasured tokens of continuity — faces carried across oceans, reminders of rituals and places that distance threatened to erase.

As communities settled into new homelands, the camera became a way to shape identity. Dressed in their Sunday best, Indo-Caribbean families posed for pictures to mark weddings, births, and new homes — images that said not only we are still Indian but also we belong here now. Albums were guarded like family treasures, their pages passed from one generation to the next. Photography became both anchor and guide — a way to hold on to India while also defining what it meant to be Indian in the diaspora.

Indian-origin social worker Grace Deoki in Fiji | Photo Courtesy: Deoki Family History Page/Facebook

As Indians settled across the world, photographs became the thread that held their lives together. In East Africa, families dressed in their best and posed for portraits that were later hung in living rooms as signs of arrival. In Britain and Canada, wedding albums connected relatives across oceans, the images shared like letters of reassurance. In the Gulf, school photos and studio portraits were sent home in brown envelopes as proof of hard-won success. And in America, Polaroids of first cars, new houses, and children born abroad filled albums that were shown on every visit back to India. For the diaspora, photographs were more than keepsakes — they were proof of survival, symbols of dignity, and memory made real. They carried identities across borders and, in the simple act of sharing a picture, affirmed: this is who we are, this is where we belong.

Portraits of Arrival: NV Parekh in Mombasa

This desire for self-fashioning is perhaps nowhere more vivid than in the work of N. V. Parekh, who ran the Victory Studio in Mombasa from the 1940s. His sitters — Indians, Africans, Arabs — arrived in their best clothes, standing before painted backdrops with pride. For many, it was the first photograph they had ever taken, and it meant a great deal.

Born into a Gujarati immigrant family in Kenya, Parekh soon became the photographer many Indians and Africans turned to. His pictures — men in suits, women in bright saris under studio lights — were more than portraits. They were statements of belonging.

Photo courtesy: NV Parekh

“Look at the light, the glow,” one sitter, Mrs. Uweso, later recalled of her portrait. “It looks as if I was floating in another world. I am sparkling. And the focus is simply on me.” In those moments before Parekh’s camera, she said, “all things became attainable.”

In colonial East Africa, where belonging was uncertain, sitting before Parekh’s camera was a way of saying: I am here, I matter. His archive of over 10,000 images shows a community in transition, shaping its identity while the idea of home was changing. His portraits reveal how photography helped Indians in the diaspora see themselves in new ways.

The Personal is Political: Sunil Gupta in London

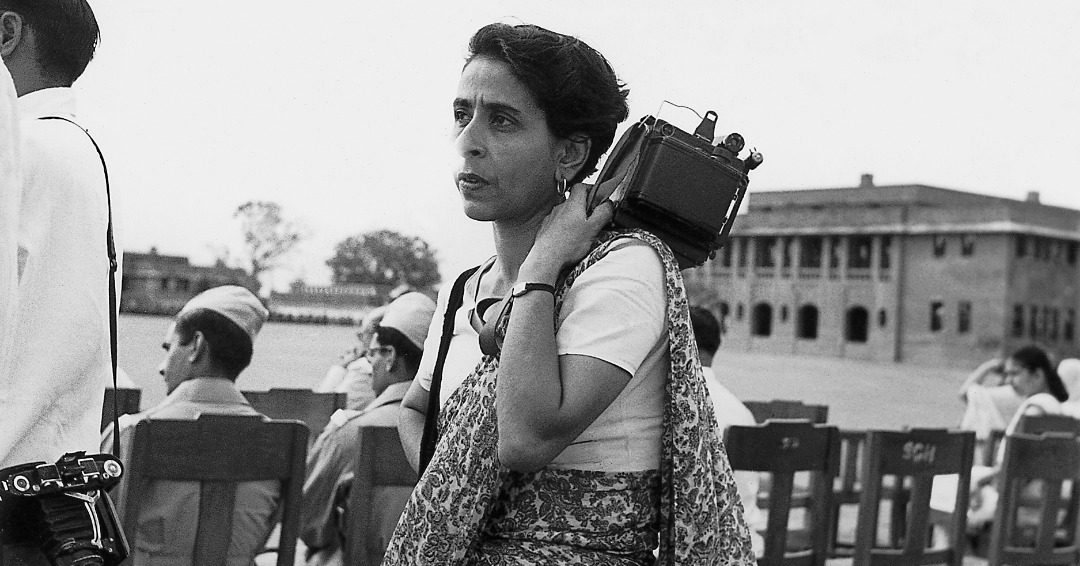

Half a century later, across the seas in London, Sunil Gupta was also using the camera to carve space for an identity rarely acknowledged. Born in Delhi, raised in Canada, and later based in the UK, Gupta found himself doubly marginalised — as a migrant and as a gay man. “Nobody else was photographing the gay life,” he said of his early years. “So I thought of doing it myself.”

His series Exiles (1986) showed gay men in Delhi, quietly holding hands before Mughal monuments, at a time when homosexuality was still criminalised. Gupta explained: “It became imperative to create some images of gay Indian men; they didn’t seem to exist.” By placing queer bodies within India’s historic landscape, he rewrote both the archive of sexuality and the archive of the diaspora.

Photo Courtesy: Sunil Gupta

For Gupta, the personal was always political. “It had always seemed to me that art history seemed to stop at Greece and never properly dealt with gay issues from another place,” he explained. “It became imperative to create some images of gay Indian men; they didn’t seem to exist.”

For him, photography was both memory and statement. His camera traced his journeys through Delhi, Montreal, New York, and London, while also creating an archive of queer Indian life that outlived laws and prejudice. In the 80s, being a queer in India wasn’t acceptable and he moved abroad. By the 90s’, he became part of the great Indian diaspora. “To distance myself from it, I focused my research and work in other parts of the world; Australia, South Africa, Malaysia. Home became London, that melting pot of Diasporas. Gays there came in all shades of skin tone and ethnic origin,” he wrote on his website.

Gupta’s work shows that diaspora identity is not only about geography but also about who is visible and who is remembered.

Still Arriving: Miraj Patel’s Anti-Road Trip

For younger diaspora voices, the question of belonging remains unresolved. Miraj Patel, a first-generation Indian American, has built his practice around the feeling of always being in-between. “My photography and art making is a process of doing and undoing, an exploration of my lineage, memory, and identity,” he has said.

In his series The Anti–Road Trip, Patel drove east across the United States — reversing the classic myth of the American road trip. “It’s the anti-road trip,” he explained. Inserting himself into American landscapes, Patel staged images that questioned who gets to belong in these spaces.

Photo Courtesy: Miraj Patel

“I was motivated to insert myself into the landscape and lore of a country that I simultaneously belonged to and felt erased in,” he has said. The result is a body of work that reflects the diaspora’s constant state of “still arriving” — always seeking space and questioning what it means to belong.

A Diaspora in Dialogue

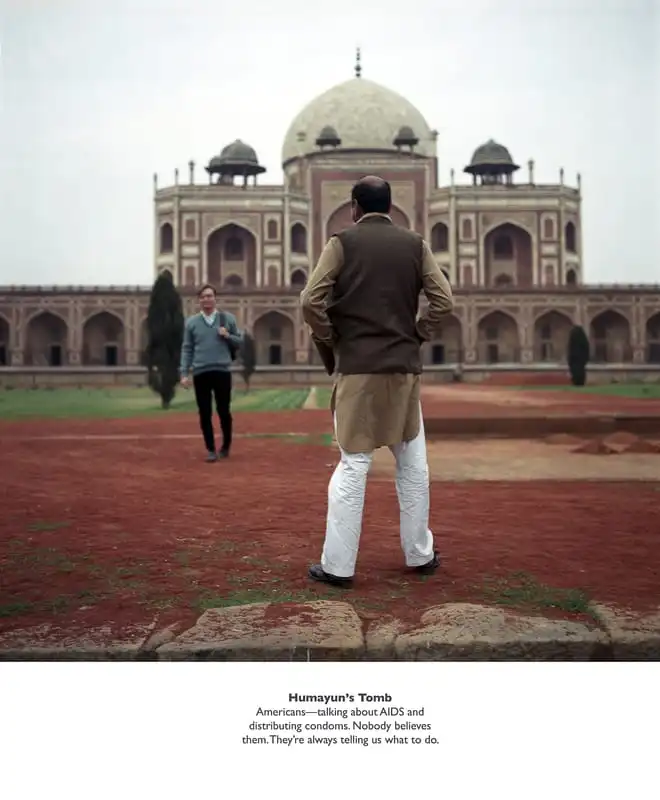

Where Gupta and Patel turn the lens inward, Gauri Gill used it to build a collective album of diaspora life. Best known for her decades-long work with rural communities in Rajasthan, Gill also created The Americans (2000–2007), a series documenting Indian diaspora families in the US in the years after 9/11.

She photographed friends and relatives in temples, kitchens, and grocery stores – everyday scenes that revealed what it meant to be Indian abroad. “Objects, clothing, architecture, light” — these, Gill says, are what show how immigrants “stand out in a new country” and what they “miss about their homeland.”

Photo Courtesy: Gauri Gill

Two women behind the counter of a Queens grocery store. Children in Halloween costumes, their parents watching with a mix of pride and hesitation. Families on suburban driveways, framed by both their new homes and the shadows of the old. Gill’s lens is empathetic, treating these images not as spectacle but as the “family album” of a community — full of memory, resilience, and quiet belonging.

By working with empathy, Gill closes the distance between photographer and subject. Her work, as one curator noted, is about “collective memories, personal histories, and dreams” — a reminder that the diaspora is made up of many stories, not just one.

Beyond Archive: The Living Legacy of Diasporic Photography

If there is a thread binding these photographers, it is their insistence that photographs are more than images — they are memory, inheritance, and selfhood. Parekh’s sitters carried dignity in colonial Mombasa; Gupta’s couples held hands against Delhi monuments; Patel placed his brown body in landscapes that once erased it; and Gill’s families, in kitchens and shops, built a quiet record of belonging.

Indian diaspora in Fiji

Together, their work shows that for the Indian diaspora, photography has never been only about recording events. It has been a way to speak across distance and time — between land and identity, memory and future. Photographs stitched lives across oceans and generations, acting as proof, as witness, and as conversation. They tell us who we were, who we are, and who we are still becoming.

On this World Photography Day, we are reminded that every photograph — whether tucked into a suitcase or hanging on a gallery wall — is more than a frame. Each one is a story of migration, memory, and the continuing search for home.

Also Read: Homai Vyarawalla: Meet India’s first female photojournalist

Also Read: Speaking of Belonging: How Indian languages shape diaspora identity across generations