(August 14, 2025) Every morning, just before the day’s first news bulletin, radios across India would come alive with a sound that became the country’s unofficial wake-up call. At 5:55 am, as All India Radio prepared to begin its daily broadcast, the gentle hum of the tanpura, also known as the tambura, would rise, steady and resonant, followed by the delicate melody of violin, viola, and cello, composed by Walter Kaufmann, a European refugee in India. In those days, when there was no television, no internet, and newspapers arrived hours later, radio was the nation’s heartbeat and the single most immediate link to news, music, and the wider world. The AIR signature tune has been more than a prelude. It was a moment of shared ritual, uniting millions of listeners in cities and villages alike. Today, while the ritual has faded, the tune endures as a living echo of the mornings of a bygone India, nostalgically remembered by radio listeners of yore.

First aired in 1936, it became as familiar as the smell of chai at dawn. Few listeners knew it was the creation of a Jewish musician who had fled Nazi Germany, found refuge in Bombay, and turned exile into an enduring gift for his adopted home that still echoes through India’s cultural memory.

Journey from Nazi Germany to the shores of India

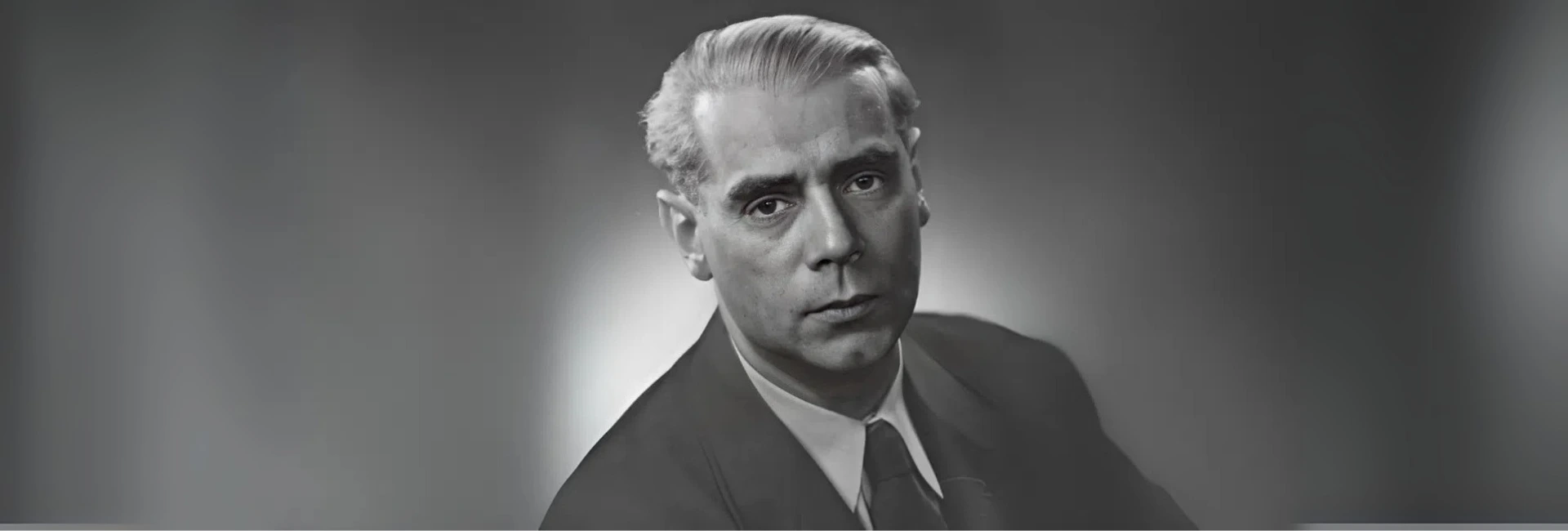

In 1934, a steamship from Europe docked at Bombay harbour carrying among its passengers a 27-year-old man with a violin case and a battered suitcase filled with sheet music. That young man was Walter Kaufmann. Born in 1907 in Karlsbad, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Kaufmann was a rising composer and conductor, trained in Prague and Berlin under masters of European classical music. But as a Jew in Nazi Germany, the world he knew was collapsing. The tightening grip of Hitler’s regime left him with few options. He had to either stay and face persecution, or flee to an unknown land. He chose India, not because it was familiar, but because it was far away from fascism’s reach. The choice would change his life, and, in a lasting way, India’s cultural history.

Laying the foundation of the Bombay Chamber Music Society

Bombay in the 1930s was a cosmopolitan hub with colonial architecture, bustling markets, British clubs, and a thriving Parsi, Anglo-Indian, and European community. It was here that Kaufmann found his first audience.

Within weeks of his arrival, he founded the Bombay Chamber Music Society, rehearsing with fellow expatriates and talented locals. They performed quartets and symphonies in spaces like the Willingdon Gymkhana, where the scent of monsoon rain mixed with the resonance of Beethoven and Brahms.

But this was no mere transplantation of European music. Walter Kaufmann was learning how to present Western classical traditions to an Indian audience, and in return, India was opening his ears to sounds and structures unlike anything he had encountered before.

All India Radio legacy

In 1936, Kaufmann’s growing reputation landed him the role of Director of Music at All India Radio (AIR) in Bombay. Established in 1930 as the Indian Broadcasting Company and reorganised as All India Radio in 1936, AIR was emerging as a powerful cultural institution, broadcasting music, news, and cultural programmes to a vast, diverse nation.

One of his earliest tasks was to create a signature tune for the station. Drawing inspiration from the rāga Shivaranjini, Kaufmann crafted a melody that began with the tranquil hum of a tambura, followed by a lyrical violin line. His friend Mehli Mehta, father of future world-renowned orchestral conductor Zubin Mehta played the violin part.

The tune was short, barely a minute long, but it became immortal. Generations of Indians woke to it; traders heard it before market updates; students hummed it on their way to school. Even today, its strains are instantly recognisable as an auditory emblem of India.

Edigio Verga (left), Walter Kauffman (centre) and Mehli Mehta (right)

From stranger to student of Indian music

Ironically, Kaufmann’s initial reaction to Indian music was one of confusion. His European training had primed him for fixed pitches, harmony, and structured notation but here was a musical tradition built on microtones, improvisation, and rhythmic cycles that could stretch and contract like breath.

Instead of retreating, Walter Kaufmann immersed himself. He studied ragas and talas, attended concerts by greats like Omkarnath Thakur, and even travelled to record folk musicians. He began incorporating Indian melodic phrases into his compositions, not as exotic ornamentation, but as authentic, structural elements.

This process which was slow, deliberate, and respectful transformed him from a European composer working in India into a cross-cultural musician whose work belonged to both worlds.

Mentor to Zubin Mehta and musical innovator

Kaufmann’s office at AIR became a hub of musical exchange. Here, Indian classical artists would meet Western-trained musicians, often collaborating on programmes that challenged both traditions.

Among those he influenced was a young Zubin Mehta, then the son of his violinist friend Mehli. Though Zubin would later find his own path in Vienna and Los Angeles, Kaufmann’s openness to musical fusion left a lasting impression.

Decades before “fusion music” became a buzzword, Kaufmann was already experimenting with orchestral arrangements of ragas, choral adaptations of bhajans, and Western compositions inspired by Indian modes.

Travels through India

Kaufmann did not confine himself to Bombay. His curiosity took him across the country to places like Madras (now Chennai), where he studied Carnatic music; Calcutta, where he encountered Rabindranath Tagore’s poetic compositions; and to Kashmir and Ladakh, where he recorded Buddhist chants and shepherd songs.

One notable creation from these journeys was “Madras Express”, a playful orchestral work evoking the rhythm of train travel and the colours of South India. Performed decades later in New Delhi, it captivated audiences with its blend of Indian motifs and Western symphonic texture.

A decade in India of finding a refuge, laboratory and home

From 1934 to 1946, Kaufmann’s Indian years were a laboratory of cultural synthesis. He composed works based on ragas, documented folk traditions, and published scholarly notes on Indian music’s complex rhythms and tonalities.

In many ways, he was an ethnomusicologist before the discipline was formally established, treating Indian music not as a curiosity but as a living, evolving art worthy of study and global recognition.

Scholar of ragas, composer for the Indian silver screen

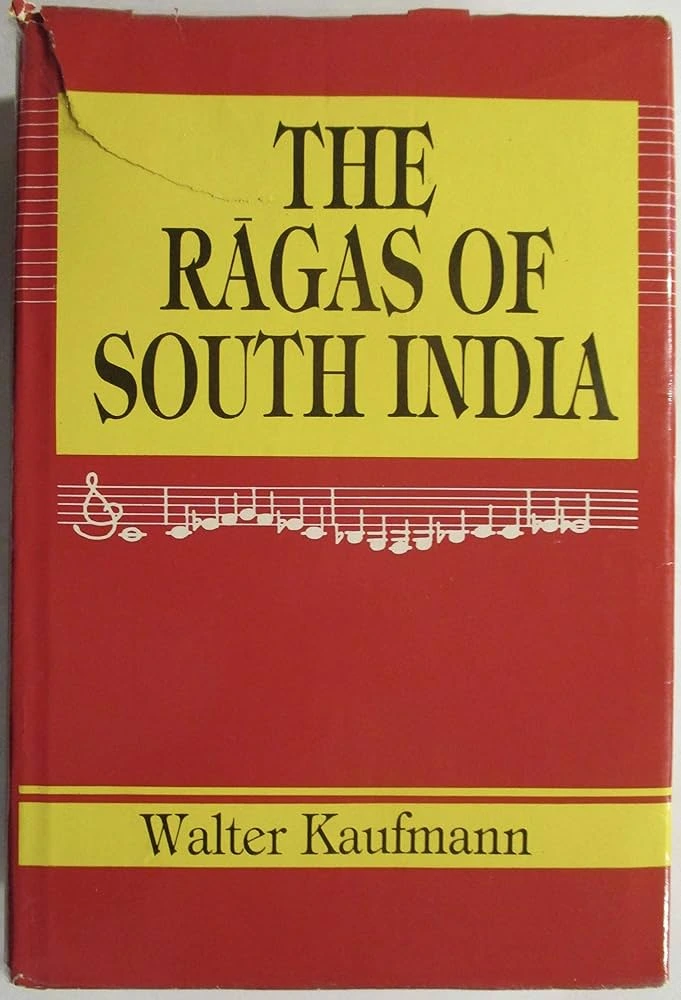

Walter Kaufmann’s Indian years comprised live performance and radio innovation. They also also created lasting contributions to music scholarship and cinema. Drawing on his deep immersion in the subcontinent’s traditions, he authored seminal works such as The Ragas of North India (1968) and The Ragas of South India: A Catalogue of Scalar Material (1976), both of which remain important references for students and performers of Indian classical music. His Musical Notations of the Orient (1967) examined notation systems across Asia, while Selected Musical Terms of Non-Western Cultures offered a glossary for scholars navigating diverse traditions.

Walter Kaufmann also published detailed field studies on India’s folk and tribal music, including the songs of the Gond and Baiga communities, and explored the performance times of North Indian ragas. Alongside his academic pursuits, Kaufmann brought his skills to Bombay’s fledgling film industry, composing for productions like Toofani Tarzan (1937) and Sohrab Modi’s Ek Din Ka Sultan (1945). In an era when radio and cinema were the most powerful cultural forces in India, Kaufmann’s writings preserved the country’s musical heritage while his film scores brought it to the big screen, blending his European training with a growing mastery of Indian forms.

Albert Einstein’s endorsement

In 1938, Walter Kaufmann received an extraordinary letter of recommendation from Albert Einstein. The physicist who was himself a refugee, and an amateur violinist, praised Kaufmann’s inventiveness, his mastery of Eastern music, and his ability to teach and conduct. Einstein wrote that Kaufmann was “highly qualified to direct choirs or orchestras, in academic or cultural institutions anywhere in the world.”

This was no casual note, rather a recognition of a kindred spirit, a fellow exile who understood the resilience and adaptability required to create anew in foreign lands.

Leaving India, carrying India

Just before India’s independence in 1946, Kaufmann moved on, first to London, working for the BBC; then to Canada, where he conducted the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra; and finally to the United States, where he joined Indiana University Bloomington as a professor of ethnomusicology.

But his connection to India endured. He composed “Six Indian Miniatures” and orchestral suites based on ragas he had studied in Bombay. His personal archives were filled with field recordings, photographs, and handwritten scores and were preserved at Indiana University’s Cook Music Library, a treasure trove for researchers.

Rediscovering a forgotten genius

For decades after his death in 1984, Kaufmann’s name was largely absent from India’s public memory, even as his AIR tune continued to play.

In recent years, however, musicians and scholars have begun to reintroduce his work to new audiences. His Indian-inspired compositions have been performed in Delhi, Berlin, and New York; his recordings have been digitised; and his story is being retold as an example of how cultural cross-pollination enriches both host and guest.

The enduring sound of a refugee’s gift

Every morning, somewhere in India, the AIR signature tune still drifts out of the radio. It lasts only a few seconds, but behind it lies a saga of exile, adaptation, and creativity.

Walter Kaufmann’s journey to India was born of necessity, but what he found in the country was a second home, and a place where he could reinvent himself, give freely of his talent, and leave a gift that would outlive him by generations.

Also Read: The rhythm divine: Ustad Zakir Hussain, the tabla virtuoso whose music bridged continents

Also Read: Mirra Alfassa: The French-born visionary who dreamed India’s most global township