(February 3, 2026) Once a student struggling in an English-medium Indian classroom, Veerabhadran Ramanathan went on to advise Pope Francis on climate change, receive the world’s highest honours in climate science, and be celebrated through RamFest, a symposium held in his name in the United States.

The 2026 Crafoord Prize, awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to Veerabhadran “Ram” Ramanathan, traces the arc of a career that transformed how climate change is analysed and explained. The citation recognises his discoveries on aerosol particles, short-lived climate pollutants, and non-carbon dioxide greenhouse gases. His work, as the Academy noted has “laid the foundation for our understanding of how small particles and gases that accumulate in the atmosphere contribute to climate change.”

Valued at eight million Swedish kronor (about US$900,000), the prize places Ramanathan in a rare scientific lineage. The Crafoord is conferred by the same academy that awards the Nobel Prize, created to recognise fields not covered by the Nobel categories.

For Ramanathan, the recognition landed with emotional force. “I was speechless and humbled,” he said, calling the award an “overwhelming confirmation that climate science is based on fundamental scientific principles backed by impeccable observations.”

It is a striking moment for a man whose life’s work has often involved questioning consensus, resisting simplification, and refusing to accept authoritative pronouncements without personally testing them. That instinct to distrust certainty until it has been interrogated, was forged much earlier, in Indian classrooms where language itself became a barrier, and in an engineering job he openly despised.

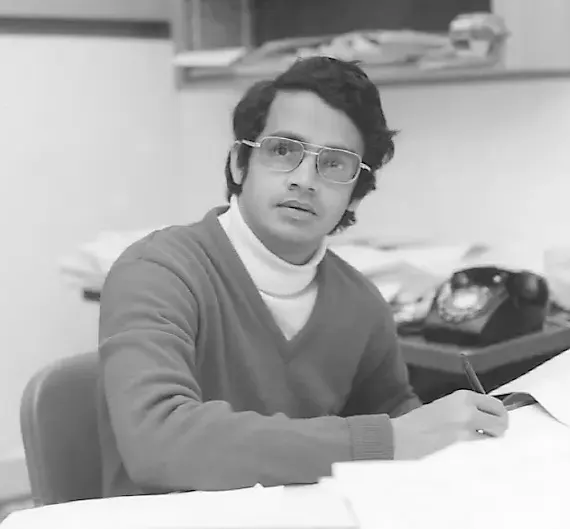

Veerabhadran Ramanathan

Losing the language, finding the method

Born in Chennai in 1944 and raised partly in small towns before moving to Bangalore at the age of 11, Ramanathan’s early education unfolded across languages and social worlds. Until high school, his schooling was in Tamil. Bangalore, a city shaped by British military administration, meant English-medium education leading to a sudden collapse in confidence.

“I quickly dropped from the top of the class to the bottom of the class,” he has recalled. “I didn’t know what they were talking about.” The consequence was not academic retreat, but intellectual independence. “I stopped learning from others. I stopped listening to my teachers because I didn’t understand what they were saying, so I had to figure out things on my own.”

That habit of learning by reconstruction rather than reception never left him. Poor grades kept him out of India’s most prestigious engineering colleges. He attended a second-tier institution, earned an undergraduate engineering degree, and took a job in the refrigeration industry. It was, by his own admission, a miserable period.

“I hated my job and I hated engineering,” he said. “I also didn’t have too much confidence that I was good for anything.”

Yet that job of diagnosing why refrigerants were leaking so rapidly from refrigeration units in Indian conditions would later become one of the most consequential experiences of his scientific life. At the time, he could not have known that the very chemicals he was trying to contain would one day place him at the centre of global climate science, or carry him into conversations at the highest levels of science, policy, and ethics.

A detour that changed everything

The turning point came with his admission to the Indian Institute of Science for a master’s degree, which was applied largely, he admits, as a way to get to the United States. Like many young Indians of his generation, America loomed large in his imagination, shaped by glossy Goodyear brochures his father brought home from work.

“They had these beautiful Impala cars,” he said. “I thought, ‘I need to go to the U.S. and own one of these cars, and enjoy the good American life. I think the story in my head was that milk and honey would be dropping out of the trees.”

Instead, IISc redirected him away from coursework. His grades were still not strong for a research track, and he was assigned what he now calls, in retrospect, an almost impossible task: building a high-precision interferometer from scratch to study turbulence. “It took me three years, but we did build an interferometer, for the first time in India,” he said. “And I learned what I am good at, which is research, and doing things which others give up as not possible.”

The experience restored confidence. It also confirmed that Ramanathan was not meant to be an engineer in the conventional sense. He was a problem-builder, not a problem-solver.

Veerabhadran Ramanathan in his younger days

From planetary atmospheres to earth

In 1970, he arrived in the United States to pursue doctoral studies at the State University of New York. His adviser, Robert Cess, pivoted away from engineering to planetary atmospheres just as Ramanathan joined his lab. The timing was perfect.

“So that’s where my work was—reconstructing the greenhouse effects on Mars and Venus, where they have pure carbon dioxide atmospheres,” Ramanathan said. The work grounded him in radiative transfer and atmospheric physics. These tools would soon prove decisive. After completing his PhD in 1974, Ramanathan struggled to find a position in planetary science. NASA eventually hired him into its re-entry physics division, tasking him with building atmospheric models.

While reading the literature, he encountered a Swedish Academy report asserting that carbon dioxide was the only human-produced gas of climatic concern. Instinctively, he doubted it. “I still never believe anything I read or what others tell me unless I can try it out myself,” he said.

Around the same time, he came across a paper by Mario Molina and Sherwood Rowland on chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and ozone depletion. The connection was immediate, and personal. “And it was the CFCs that I was trying to prevent from escaping in my job in India,” he said. Against the advice of senior figures including his former adviser, who told him he was “wasting his time”, Ramanathan ran the calculations. The results were staggering: CFCs trapped heat nearly 10,000 times more effectively per molecule than carbon dioxide.

That single insight transformed climate science. Atmospheric chemistry was no longer peripheral; it was central. The paper brought Ramanathan into the mainstream of the field, read by future Nobel laureates and reviewed by leaders of the US National Academy of Sciences. From “an obscure guy from India,” as he puts it, he became indispensable.

Measuring the invisible

Through the 1980s, Ramanathan played a pivotal role in NASA satellite missions, including the Earth Radiation Budget Experiment (ERBE), which directly measured how much energy Earth absorbs and emits. These observations demonstrated that without reliance on climate models, human-produced greenhouse gases were trapping increasing amounts of outgoing heat.

Veerabhadran Ramanathan in Maldives with aerial vehicles to measure pollutants in South Asia’s brown clouds

After joining the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in 1990, his work widened further. He investigated hydrofluorocarbons, atmospheric aerosols, and the climatic role of clouds. Perhaps most influential were his large-scale field experiments over the Indian Ocean.

The Indian Ocean Experiment (INDOEX) revealed something deeply unsettling. Vast plumes of pollution—what Ramanathan termed “atmospheric brown clouds” were stretching thousands of kilometres from land, absorbing sunlight, heating the atmosphere, weakening monsoons, and accelerating Himalayan glacier melt. The pollution was not incidental. It was anthropogenic, persistent, and global.

This work directly shaped international climate policy, helping spur efforts to reduce short-lived climate pollutants through mechanisms such as the UN Environment Programme’s Climate and Clean Air Coalition. It also reframed climate action as something that could deliver near-term benefits, not just distant ones.

The India he never left behind

While Ramanathan was engaged in groundbreaking work abroad, his engagement with India has never been limited to observation from afar; it has repeatedly translated into interventions designed at the scale of everyday life. One of the most consequential was Project Surya, launched in 2007 to address the intertwined challenges of air pollution, public health, and climate change in rural India. The initiative emerged from his research linking atmospheric brown clouds over the Indian Ocean to biomass cooking and household combustion, and it also carried a memory from his own childhood.

Veerabhadran Ramanathan while working on Project Surya in Indian villages

Growing up, Ramanathan watched his grandmother cook over firewood in an enclosed kitchen, only later recalling how she would cough relentlessly after every cooking session, without anyone making the connection to the smoke filling the room. It was only decades later, as the science became clear, that the personal and the planetary converged. “Then I thought, this is a problem I can solve,” he said, recognising that humanity had already learned how to cook without producing smog.

Project Surya operationalised that insight by introducing cleaner cookstoves and solar lighting in Indian villages while directly measuring reductions in soot and carbon emissions. In doing so, it reframed climate action not as an abstract global imperative, but as a practical, humane solution rooted in health, livelihoods, and dignity.

Science, conscience, and the Vatican

Ramanathan’s influence eventually crossed an unlikely threshold with the Vatican. Appointed to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in 2004, he became one of the key scientific advisers to Pope Francis on climate change and was influential in shaping Laudato si’, the papal encyclical on the environment. It was an extraordinary arc from a Tamil-medium schools and leaky refrigerators to advising the moral authority of the Catholic Church on planetary ethics.

For Ramanathan, the connection made sense. Climate change was never just a technical problem. It was, fundamentally, a question of justice, responsibility, and intergenerational ethics.

The measure of a career

In September 2025, US-based Scripps Institution of Oceanography hosted RamFest, a symposium celebrating Ramanathan’s career and retirement. The Ramanathan Climate Conversation, now an annual event, has become a space where science, policy, and moral urgency intersect.

By then, the honours were already extensive: membership in the US National Academy of Sciences, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Tang Prize, the BBVA Frontiers of Knowledge Award, the Grande Médaille of the Académie des sciences, and the Champions of the Earth Lifetime Achievement Award, among many others.

The Crafoord Prize, however, feels like something else. Not a capstone, but a clarification. It affirms that climate science that is often politicised, misrepresented, or diluted, rests on rigorous observation and hard-earned understanding.

Veerabhadran Ramanathat with Pope Francis, the 266th Bishop of Rome

For Ramanathan, who once stopped listening because he could not understand the language being spoken, it is a powerful symmetry. His life’s work has been about making the invisible visible, about refusing easy answers, insisting that the atmosphere, like truth, reveals itself only to those willing to look closely, and that the planet does not need belief. It needs attention.

Major awards and recognitions bestowed on Veerabhadran Ramanathan before the Crafoord Prize 2026

- Grande Médaille, Académie des sciences (2024) – France’s highest scientific honour, recognising lifetime contributions to atmospheric and climate physics.

- Tang Prize for Sustainable Development (2018) – Often described as Asia’s Nobel, awarded for showing how cutting short-lived climate pollutants can slow global warming in the near term.

- BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award (2015) – One of the world’s leading science prizes, honouring his discovery that non-CO₂ human pollutants profoundly alter Earth’s climate.

- Pontifical Academy of Sciences (2004) – Appointed to advise the Vatican on climate change, linking climate science to global ethical and policy discourse.

- Carl-Gustaf Rossby Research Medal (2002) – The highest honour in atmospheric science, recognising foundational insights into clouds, aerosols, and key climate-forcing gases.

- US National Academy of Sciences (Elected 2002) – Peer recognition for landmark contributions to understanding human impacts on the climate system.