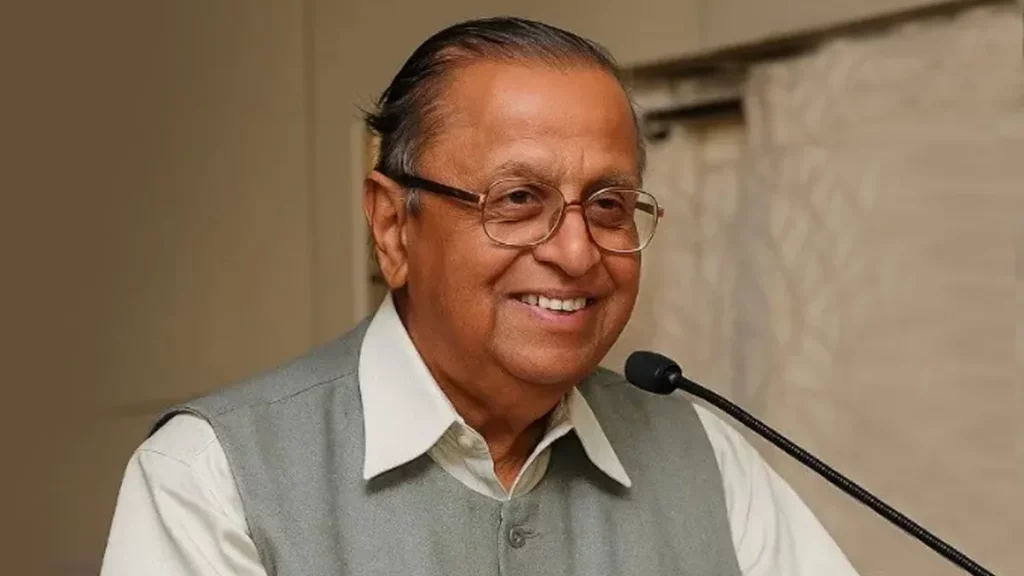

(November 12, 2025) Vaidyeswaran Rajaraman, who passed away on November 8 at the age of 92, was the pioneer of computer science education in India and a mentor to future industry leaders like N.R. Narayana Murthy, the founder of global IT giant Infosys. Widely regarded as the father of computer science education in the country, Rajaraman launched India’s first academic program in the field at IIT Kanpur in the 1960s and inspired a generation of engineers who would go on to shape the nation’s IT revolution.

In the early 1960s, few in India believed computers would shape the nation’s destiny. The idea of teaching “computer science” seemed extravagant, even absurd, in a country still finding its scientific footing. Yet, amid that skepticism, one moment captured the dawn of a new era, and that wa a massive IBM 1620 computer, transported to IIT Kanpur on a bullock cart.

The sight was both comical and prophetic. Here was a symbol of old and new India moving together with an ancient vehicle carrying a futuristic machine.

It was a perfect symbol of old and new India moving together, the traditional carrying the technological. For a young professor named Vaidyeswaran Rajaraman, it marked the beginning of a revolution in education. Though IIT Kanpur was among the newer IITs at the time, it became the most daring and experimental, and a living laboratory of ideas where Indian and American collaborations planted the seeds of modern engineering and computer science education. Years later, Rajaraman would look back with pride, calling the Computer Science department at IIT Kanpur “his baby.”

The IBM 1620, being carried to IITK on a bullock cart | Photo Credit: Vox Populi, IIT-Kanpur

From Erode to MIT: The making of a visionary

Born in 1933 in Erode, then part of the Madras Presidency, Vaidyeswaran Rajaraman grew up in a family that valued learning and perseverance. His parents, Ramaswami Vaidyeswaran and Sarada, nurtured his early interest in science. He studied at the Madras Education Association School in New Delhi, passing his Higher Secondary exam in 1949 as part of its very first batch. A Delhi University scholarship took him to St. Stephen’s College, where he earned a B.Sc. (Honours) in Physics in 1952. Fascinated by electronics, he joined the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bangalore, earning a Diploma in Electrical Communication Engineering in 1955 and later an Associateship for his work on analogue computers.

His academic brilliance won him an overseas scholarship, leading him to MIT, where he completed a Master’s in Electrical Engineering in 1959, and then to the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where he earned his PhD in 1961 for his pioneering research in adaptive control systems. Returning to India in 1962, he joined IIT Kanpur as one of its earliest faculty members. A year later, he married Dharma, who remained his steadfast partner through decades of teaching and institution-building.

A campus with no buildings but boundless vision

When V. Rajaraman joined IIT Kanpur in 1963, there was little to suggest it would become the cradle of Indian computing. “There was nothing at the Kalyanpur campus at the time,” he recalled in an interview with Vox Populi, the student magazine of IIT Kanpur. “We were based out of the HBTI campus. HBTI had given IIT one little wing to begin. There was one room where all the Electrical Engineering faculty sat.” Harcourt Butler Technical Institute (HBTI), one of Kanpur’s oldest technical institutions established over a century ago had temporarily hosted the fledgling IIT in its early years.

That single room held a handful of determined teachers and an even smaller number of students. “I was the first Assistant Professor to join the department; everyone else was a lecturer,” he said. The institute’s first batch moved to the new campus on April 1, 1963 — “April Fools’ Day,” as Rajaraman fondly remembered and endured the summer heat with minimal facilities. But what they lacked in infrastructure, they made up for in imagination. And when the IBM 1620 arrived later that year, it gave substance to that imagination.

The machine that changed everything

The IBM 1620, a powerful transistorized computer, was among the most advanced of its time. In August 1963, it became the first computer ever installed in an Indian educational institution, and it made IIT Kanpur the pioneer of computer-based teaching in the country. “We planned on keeping the 1620 in the Western Laboratories building; however, the door wasn’t big enough to accommodate it; we had to break down a wall to bring it in,” Rajaraman said. The episode symbolized the spirit of those early years: breaking literal and figurative walls to introduce new knowledge. The 1620 came equipped with a Fortran compiler, enabling students to write high-level programs. It was a radical shift from traditional engineering problem-solving.

To help set it up, a team of three American professors arrived, led by computer science pioneer Dr. Harry Huskey of the University of California, Berkeley. “Huskey wanted to teach computer programming to all the faculty,” Rajaraman recalled. Thus began India’s first intensive programming course which comprised ten days of lectures attended by 60 researchers and teachers from across the country. “A three-hour lecture was held every morning. One hour on programming, one hour on numerical methods, and one hour on computer logic,” he said. “Three batches of 20 were formed to write programs on the 1620 because there were only 20 punching machines available. It was a very tedious task and required a lot of patience.” In that modest workshop, India’s computer science story had begun.

TA 306: The first computer programming course in India

By 1965, the American professors had returned home. Rajaraman and his colleagues took the next step: launching India’s first formal computer programming course, known as TA 306. “The course was a Technical Arts course because, in those days, the computer was seen as a ‘tool in a workshop’ and not as a ‘science’,” he explained. The course introduced generations of IIT students to the logic and language of computing and sowed the seeds for a brand-new discipline.

A ₹5 textbook that empowered a generation

While teaching TA 306, Rajaraman noticed another problem. “American textbooks were quite expensive,” he said. As a solution, he wrote his own. Titled Principles of Computer Programming, it was printed in IIT Kanpur’s Graphic Arts section and sold for just ₹5. “The book became quite popular, and I found out that it was being plagiarised,” he laughed. His wife suggested publishing it formally, but publishers turned him away. “They believed the book would never sell.”

Finally, Prentice Hall agreed to publish a low-quality edition in 1969. “Contrary to the publisher’s apprehensions, within a year, the first edition was sold out,” he said. The 1970 reprint was of better quality but still modestly priced at ₹15. The book became a standard across India and the first indigenous textbook on computer programming.

The birth of a department

As student interest surged, Rajaraman pushed to formalize the subject. In 1965, IIT Kanpur introduced a master’s option in Computer Science under the Electrical Engineering Department. “The option became very popular with the students,” he said. But not everyone was pleased. “The Electrical Department was unhappy over the declining interest of students in other fields of the department.”

In 1972, the Senate approved an exclusive master’s programme in Computer Science. “The first batch had about 15 students,” he remembered. “TCS hired almost every student in that batch.”Faculty shortages made it an uphill climb. “Prof. H.N. Mahabala, Prof. Narsingh Deo and I shouldered the entire weight,” Rajaraman said. “In 1973, we were in for a big shock. IIT Madras got its hands on an IBM 370, and Dr. Mahabala, along with some other faculty members, left for Madras.” Still, Rajaraman persevered, shaping a new department brick by brick.

The fight for a B.Tech in computer science

By 1976, he was ready to propose a full-fledged B.Tech programme in Computer Science and Engineering. This idea met immediate resistance. “The Senate did not look favourably upon it. Their view was that it was a vocational course and did not require a bachelor’s programme,” he said.

To start the course, other departments had to sacrifice seats. “They grudgingly gave up 2–3 seats each and 20 seats were allocated to us,” Rajaraman recalled. The first batch was admitted in 1978.Convincing students and parents was another challenge. “They were very apprehensive about this new programme,” he said. One of his students was Rajeev Motwani who went on to become a professor of computer science at the Stanford University. “His father, who was a naval officer, came up to me and enquired about whether there was any future in Computer Science. I succeeded in convincing people that it was a growing area and held tremendous amounts of potential.” When the JEE results came out, the new Computer Science programme closed at an All India Rank of 40. “This made everyone, including the other IITs, who didn’t have computer science programmes, take notice,” Rajaraman recalled.

“At that time, the IITs did not have an official sanction from the ministry to set up a new department to offer a B.Tech in Computer Science; we had done so through ‘devious’ means.” It was a small act of defiance that forever changed Indian education. All five IITs soon followed suit, formally creating their own departments of Computer Science and Engineering.

Beyond IIT Kanpur: Shaping India’s computing ecosystem

In 1982, Rajaraman moved to the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, where he founded the Supercomputer Education and Research Centre (SERC). His focus turned to low-cost parallel computing and the creation of India’s early supercomputing facilities. He chaired SERC until 1994, guiding research that helped lay the groundwork for later national projects like the Centre for Development of Advanced Computing (C-DAC) and the PARAM supercomputers.

During his career, he guided PhD students, published over 70 papers, and wrote 23 textbooks covering everything from FORTRAN to e-commerce technology. His monograph, History of Computing in India: 1955–2010, commissioned by the IEEE Computer Society, remains the most comprehensive chronicle of India’s IT journey. He also played a pivotal role outside academia, designing training modules for Tata Consultancy Services, helping shape the AICTE computer science curriculum, and chairing the committee that introduced the MCA programme to meet India’s growing IT manpower needs.

As a member of the Electronics Commission, he recommended the creation of C-DAC and advised the Government of Karnataka on several e-governance projects, including the Bhoomi and Kaveri systems.

The teacher who saw the future

Over time, Rajaraman’s students would go on to build the companies and institutions that defined modern India. Rajaraman remained an educator first. He always believed that students should ‘get their hands dirty’ and indulge in project-oriented work, and that “they must also understand the history and evolution of computers to be able to appreciate the advances in computer science.”

Vaidyeswaran Rajaraman’s life’s work was recognized with some of India’s highest honors — the Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Prize in 1976 for his pioneering research, the Padma Bhushan in 1998 for distinguished service to science and engineering, the Homi Bhabha Prize, and the Om Prakash Bhasin Award, among many others. Elected fellow of all major Indian science academies, he was also honoured with the lifetime achievement awards from the Computer Society of India, Dataquest, and the Systems Society of India. For the man who helped a nation take its first steps into the digital age, computer science was not the privilege of a few, but the language of an entire generation.

ALSO READ: Remembering former PM Dr Manmohan Singh, the architect of Brand India’s growth story

I was privileged to be associated with Prof. Rajaraman for nearly two decades. His keen intellect and valuable insights, a broad smile and a great sense of humour were always welcome.

He loved to engage in discussions on technology. While I was never taught by him at IISc, I found him to be a wonderful teacher outside the classroom.

May Prof. Rajaraman rest in eternal peace.