(August 15, 2025) On a summer day in 1907, far from home, an unusual moment took place in Stuttgart, Germany. Bhikaji Cama, an Indian living abroad, walked onto the stage at an international socialist conference and unfurled a flag she called the flag of independent India. Dressed in a saree, the Parsi-born activist declared, “This is the flag of India’s independence!”—decades before that dream would come true. The crowd was stunned. At a time when British rule seemed unshakable, her act on foreign soil lit a spark of hope. It was proof that the fight for India’s freedom was not limited to its borders. As India marks its 79th Independence Day, it’s worth remembering that overseas Indians were also at the heart of the struggle—raising their voices, collecting funds, and even building armies for the cause.

Fast-forward to the present: the Indian diaspora is often hailed as a “living bridge” between India and the world, celebrated for its entrepreneurial success and cultural influence. But over a century ago, this same diaspora was a lifeline for the independence movement. In colonial times, Indians living abroad – from London to San Francisco, Paris to Singapore – became active campaigners for independence. They started revolutionary groups, published newspapers, formed lobbying networks, raised funds for nationalist causes, and even took up arms. “The Indian diaspora’s endeavour in the freedom struggle of India is less known. It is essential to recognise its efforts… otherwise as a nation we shall fail in paying due homage to our freedom fighters in entirety,” writes scholar Neerja A. Gupta, calling for overdue recognition of these patriots. The destiny of India and its diaspora has always been connected, and their passion for the motherland built a powerful, if often overlooked, global front in the fight against British rule.

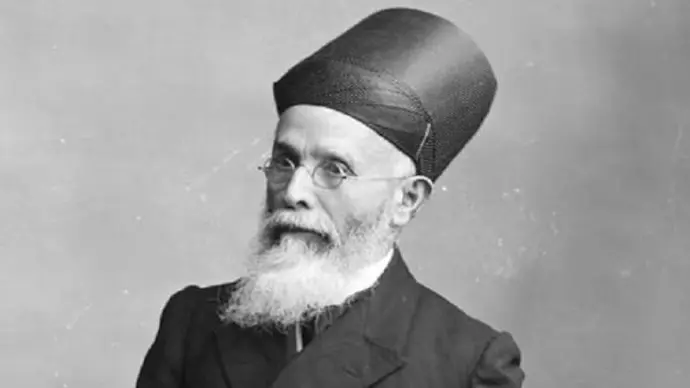

Bhikaji Cama

Seeds of Freedom on Foreign Soil

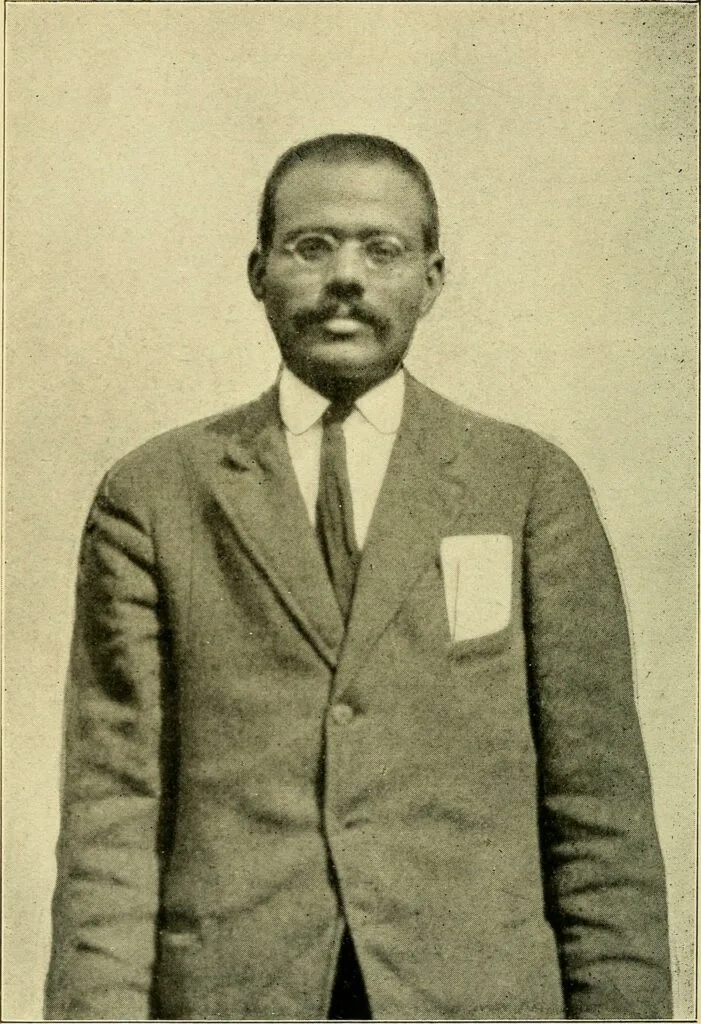

Diaspora activism in the freedom struggle began in the late 19th century. Under British rule, many educated Indians went to Britain for higher studies or work, and some stayed on to fight for India’s rights. In London, Indians became early supporters of self-rule. The most famous was Dadabhai Naoroji, the first Indian elected to the British Parliament in 1892. He used his position to expose Britain’s exploitative policies in India, calling them “un-British rule,” and argued for self-government. Around the same time, leaders like Womesh Chandra Bonnerjee and Badruddin Tyabji worked through the British Committee of the Indian National Congress to influence public opinion in Britain. These early overseas leaders laid the foundation for future activism. As Lala Lajpat Rai, who spent years in exile, observed in 1917, global events and opinions were already shaping India’s nationalist movement.

In London, a more radical wave of diaspora activism took shape. In 1905, Shyamji Krishna Varma, a Sanskrit scholar and lawyer, founded the Indian Home Rule Society and set up India House in Highgate, London. Intended as a hostel for Indian students, it soon became a hub of revolutionary nationalism. Leaders like Vinayak Damodar “Veer” Savarkar, V.V.S. Aiyar, and Madan Lal Dhingra met there to plan armed resistance. Varma also published The Indian Sociologist, openly calling for colonial rule to end. After Dhingra assassinated a British official in 1909, India House came under heavy watch, and Varma fled to Paris. Madam Bhikaji Cama joined him, along with Munchershah Godrej and S.R. Rana. From Paris, they printed and smuggled revolutionary literature into India, and Cama co-founded the Paris Indian Society, forging links with Irish, Egyptian, and Russian revolutionaries. Later, paralyzed in exile, Cama regretted only that she never saw India free – though her courage had already inspired a new generation of fighters.

Dadabhai Naroji

By the 1910s, Indian patriots overseas were planning to fight the British, using World War I as an opportunity. In 1914, nationalists in Europe formed the Berlin Committee, later the Indian Independence Committee, led by figures like Virendranath Chattopadhyaya, Maulana Barkatullah, Champak Raman Pillai, and Raja Mahendra Pratap. They allied with Germany and Turkey to spark revolts in India. In 1915, Pratap set up a Provisional Government of Free India in Kabul – the first government-in-exile – recognized by Germany and Ottoman Turkey. At the same time, Chattopadhyaya’s “Plan Zimmerman” aimed to send arms to India. These efforts, part of the Hindu–German Conspiracy, were foiled by British intelligence, leading to major trials in San Francisco and Lahore. Still, their daring inspired many, including a young Bhagat Singh.

“Ghadar” – Revolt from California

One of the most influential diaspora movements in the early 20th century was the Ghadar Movement in North America. “Ghadar” means “revolt,” and that was exactly its purpose. In 1913, Indian immigrants on the U.S. West Coast – mostly Punjabi Sikhs, along with Hindus and Muslims – formed the Ghadar Party in California to launch an armed uprising in India. They were ordinary people – farmers, lumber mill workers, and students – united by deep patriotism and anger at British rule. Leaders like Sohan Singh Bhakna, Lala Hardayal, Taraknath Das, and Kartar Singh Sarabha quickly mobilized the Indian community in the U.S. and Canada. They set up their base at the Stockton Sikh Temple in California and started publishing a fiery newspaper, The Ghadar, in Punjabi, Urdu, and Hindi. Every week it carried powerful editorials and reports of British oppression, urging Indians to rise up. One early issue declared, “Today there begins in foreign lands a war against the British Raj… what is needed is weapons, weapons, and weapons!” Copies were secretly sent to India, often hidden inside American newspapers, and spread rapidly. For many expatriates, especially Sikh farmers in Vancouver and California who faced discrimination, the paper gave voice to a bold belief: if India were free, Indians everywhere would win back their dignity.

Ghadar Movement

When World War I broke out, the Ghadar activists saw an opportunity. Hundreds of Indians living in North America quit their jobs, sold their businesses or farms, and set sail for India to start a rebellion. They worked with the Berlin Committee and German allies to get weapons. In 1915, Ghadarites like Kartar Singh and Vishnu Ganesh Pingle tried to spark mutinies among Indian soldiers in Punjab. But British spies had already infiltrated the movement. The plan failed, leaders were caught, and 42 Ghadar members were executed after the Lahore conspiracy trials. The crackdown was brutal, but it didn’t kill the spirit of the movement. Those who escaped regrouped abroad and kept fighting. In the United States, several Ghadar activists and Germans were tried in the famous San Francisco Hindu–German Conspiracy Trial of 1917 and sentenced for plotting against Britain. Even with these setbacks, the Ghadar Party continued in some form into the 1920s and 1940s, leaving behind a strong legacy of militant patriotism. Its members, scattered across the world, showed that the Indian diaspora could be a powerful revolutionary force. “From a reformist movement to an insurgent movement, the Indian diaspora’s financial and ideological assistance was part of the Indian freedom struggle,” notes one historical study. Ghadar’s story proved how Indians abroad turned their hardship and alienation into energy for India’s freedom.

Armies and Funds from Across the Seas

By the 1940s, the largest Indian communities abroad were in Southeast Asia – in British territories like Malaya, Burma, and Singapore, where many worked as laborers, traders, or soldiers. When Japan occupied these areas during World War II, Indians there had to choose: stay loyal to the British or join Subhas Chandra Bose in the fight for freedom with Japanese support. Bose, a charismatic leader who had broken from Gandhi’s non-violent path, escaped India in 1941 and reached Japan’s allies in 1943. In Singapore, he took command of the fledgling Indian National Army (INA), formed from Indian prisoners of war. Known as Netaji, he knew the diaspora’s backing was essential. His arrival “was met with widespread support from the local Indian population,” according to Singapore’s archives. In the months that followed, he staged what was called a “public relations masterpiece, gathering support – in both men and material – from the Indian diaspora in Japanese-occupied Southeast Asia.” Thousands joined him – Malay Tamils from rubber estates, Sikh traders in Singapore, Tamil Chettiars in Burma – and many women enlisted too, forming the INA’s all-female Rani of Jhansi Regiment.

Subhash Chandra Bose

Bose’s INA grew to over 40,000 troops, thanks largely to recruits and resources from the diaspora. The support was so strong that “many Indians donated their life savings for the cause.” At rallies, shopkeepers and plantation workers handed over their earnings and jewelry, inspired by Bose’s call: “Give me blood, and I will give you freedom.” In one well-known moment, Indian women in Malaya removed their gold bangles and earrings on the spot to contribute. This was more than financial help – it was an emotional pledge to see their homeland free. Though the INA, fighting alongside Japanese forces, was defeated in Burma, its impact was lasting. In 1945, when INA officers were tried for treason, sympathy for these “diaspora soldiers” swept across India. The sight of Sikh, Hindu, and Muslim INA heroes standing together in court stirred the nation. Jawaharlal Nehru even appeared as their lawyer. The resulting wave of support – which helped spark the 1946 Royal Indian Navy mutinies – convinced Britain it could no longer count on Indian troops’ loyalty. As Bose had predicted, “their sufferings and sacrifices… will serve as an undying inspiration to Indians all over the world.”

Beyond the battlefield, the diaspora also gave crucial money and influence. Since the 1880s, wealthy merchants in East Africa and Hong Kong had funded Indian causes, from famine relief to education. In Burma, Malaya, and Fiji, Indians raised money for both the Congress and revolutionary groups. In the 1920s, traders in Singapore formed “India associations” to support nationalist papers and host Congress leaders. Madam Cama used her inheritance to fund propaganda and scholarships, while Shyamji Krishna Varma offered fellowships to students who pledged to join the freedom struggle. In the U.S., Lala Lajpat Rai founded the Indian Home Rule League of America in 1917, toured the country giving speeches, and, with allies like Rev. Jabez T. Sunderland, built “Friends of Freedom for India” to rally American support.

A Legacy to Celebrate

When India won independence in 1947, the role of the diaspora was rarely mentioned in schoolbooks or popular stories. The focus was on the movements within India – Gandhi’s marches, Nehru’s speeches, and the sacrifices of martyrs at home. But the diaspora’s story is also a vital part of that history. Overseas Indians were India’s “secret weapon,” raising the call for freedom abroad when it was silenced at home. They were the unsung allies: from the “Lioness of India” Bhikaji Cama waving a banned flag in Europe, to the Ghadar fighters in California plotting revolt, to lobbyists in London and New York, to the INA soldiers marching with Bose. Their work showed that India’s fight for freedom was truly global. As historian Aparna Basu noted, the involvement of diaspora Indians – whether through “hospital funds, student scholarships, or revolutionary aid” – helped “facilitate the transition of India from colonization to independence.” In short, the diaspora was a crucial pillar of the struggle for freedom.

Lala Hardayal

Today, the Indian diaspora is more visible than ever – from Silicon Valley boardrooms to national parliaments – and celebrated as India’s “soft power.” But this influence began long before 1947, with freedom fighters across Asia, Europe, Africa, and the Americas who never forgot the “call from motherland.” They formed secret groups, raised funds, and even gave their lives for India’s liberation.

As we celebrate the 79th Independence Day, their stories remind us that the dream of freedom lived far beyond India’s borders – in the hearts of laborers in Fiji, students in Tokyo, activists in London, and workers in California. Honouring them enriches the legacy of the independence movement. These global Indians proved that patriotism has no borders, and though far from home, they kept the flame of freedom alive. Their contributions remain a proud and inspiring part of India’s story.

Also Read: Sophia Duleep Singh: The Indian princess who took on the British Empire for women’s rights

Also Read: World Photography Day: How photographs gave the Indian diaspora a sense of belonging