(August 10, 2025) When Indian immigrants were barred from U.S. citizenship, Dalip Singh Saund imagined a different future and made it real, rising from a turbaned newcomer in America to a California farmer, citizenship activist, and ultimately the first Asian elected to the United States Congress, which is the legislative branch of the U.S. federal government.

In 1920, a young Dalip Singh Saund stepped off a ship in the United States after a long voyage from colonial India, his turban neatly tied and eyes fixed on the future. His journey had taken him from Punjab to Bombay to England before arriving at Ellis Island, New York.

He came from a modest Sikh farming family in the village of Chhajulwadi, Punjab. A mathematics graduate of the University of the Punjab in Amritsar, he had convinced his family to let him pursue further studies in food canning in America. But once enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, his path shifted from food preservation to advanced mathematics, from nationalist debates to political clubs, and eventually from the agricultural fields to the halls of the U.S. Congress.

As he reflected in his memoir Congressman From India (1960), “Even though life for me did not seem very easy, it had become impossible to think of life separated from the United States.”

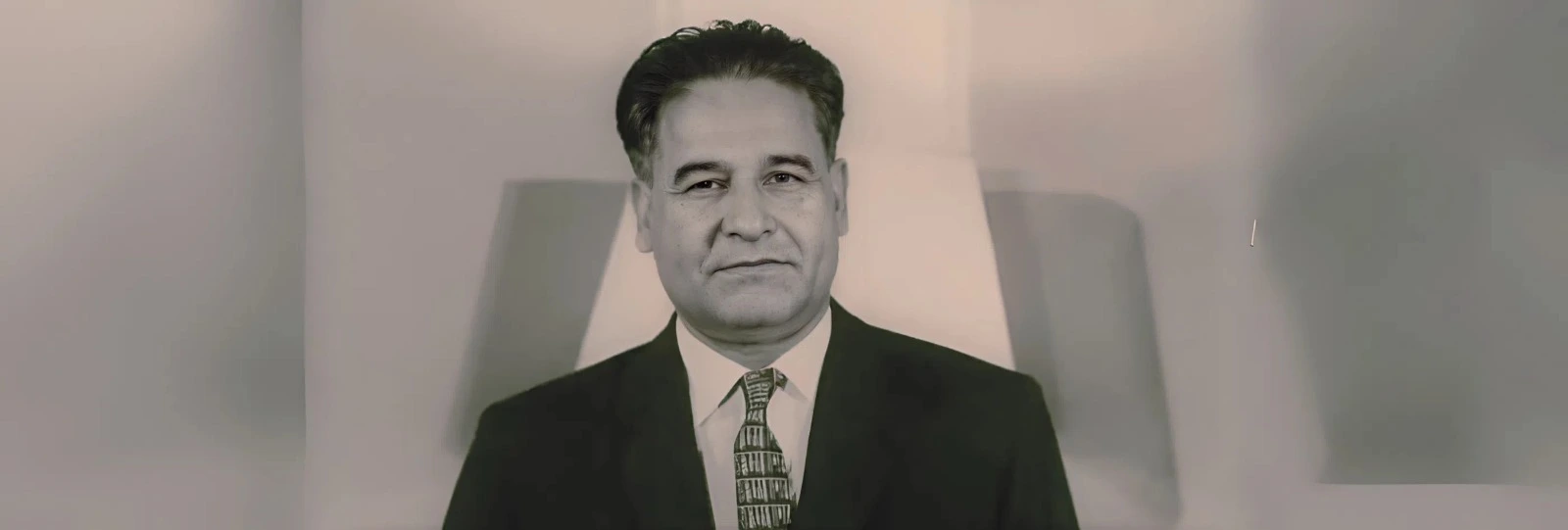

Dalip Singh Saund

Locals first knew him as the “wild Indian,” the Sikh farmer with a turban flapping in the wind as he zipped through dusty roads in his rattling Ford. In time, they began calling him “Judge Saund,” after he was elected Justice of the Peace in Westmorland, and then Congressman Saund.

I was elected by Americans, not because I am an Indian, but in spite of it.

Dalip Singh Saund

In today’s debates on immigration, race, and representation, Saund’s story feels more relevant than ever. The Indian-origin immigrant became part of American history and helped write it. During his tenure in the House of Representatives at the height of the Cold War, he emerged as one of the era’s most captivating politicians. Despite enduring significant discrimination, his faith in the promise of American democracy remained steadfast.

Punjab to Berkeley

Born in 1899 into a reform-minded Sikh family, Saund grew up in a village that valued education even when the colonial state did not. Although uneducated themselves, his father and uncles financed a local school, determined that the next generation rise through knowledge. With roots in Sikh reformism and activism, Saund inherited both a strong work ethic and a grounding in social action.

This early exposure to reformist ideals and nationalist sentiment shaped his political consciousness. During his college years in Punjab, he supported the Indian independence movement.

By 1920, with a mathematics degree in hand, he left for California intending to learn about food preservation and fruit canning. But his time at UC Berkeley changed the course of his life. He was drawn into political debate, became president of the Hindustani Association of America, and discovered a passion for public speaking and activism. Alongside his canning studies, he earned a master’s and PhD in mathematics.

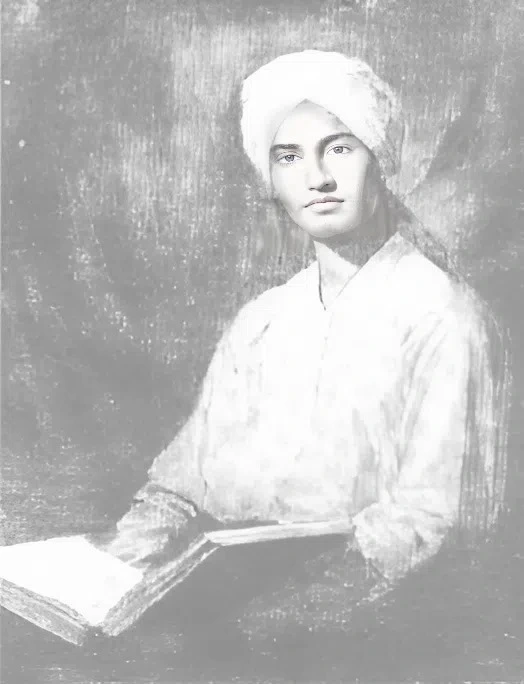

Dalip Singh Saund during his student days

Racial prejudice barred him from securing a teaching position after completing his PhD in 1924. Turning to farming in California, Saund bypassed a state law prohibiting Asians from owning land by having a friend hold the deed in his name. In 1930, the Khalsa Diwan Society commissioned him to write My Mother India, a book championing India’s independence and examining its political and cultural challenges.

Teaching posts in India were offered, but he remained committed to the American experiment. While farming, he followed U.S. politics closely, studying the presidential elections of 1924 and 1928. Witnessing the hardships of the Great Depression firsthand, he became a firm supporter of the New Deal. Throughout the 1930s, he campaigned for Indians to gain American citizenship. It was a goal that got realized a decade later.

Seeds of leadership

By the mid-1920s, Saund had settled in California’s Imperial Valley, a rugged desert region where Indian immigrants had begun farming. He started by managing a cotton-picking crew and soon saved enough to grow lettuce on his own. Early losses didn’t deter him; over time, he became a successful alfalfa and vegetable farmer.

Here, amidst the harsh sun and hard soil, Saund built both his livelihood and his political base. He joined the Toastmasters Club in Brawley, refined his speaking skills, and became district governor. He was known to irrigate fields in the evening, change into formal wear in his car, attend meetings, then return to the farm by nightfall.

He also met and married Marian Kosa, a Czech-American artist from Los Angeles. Their interracial marriage in 1928 was rare and courageous, and Marian became a stalwart supporter in Saund’s political life. Together they raised three children, balancing rural life with civic ambition.

Family picture of Dalip Singh Saund clicked in the year 1957

The people’s judge

Although active in community discussions and Democratic clubs for years, Saund’s first official political role came in 1952, when he was elected Justice of the Peace in Westmorland. He had previously won the seat in 1950 but was blocked by a lawsuit citing the technicality that he hadn’t been a citizen for a full year.

As Justice of the Peace, colloquially known as “Judge,” Saund brought integrity and reform to the role. He cracked down on Westmorland’s red-light district, sentencing offenders to jail and working with federal agents to dismantle entrenched vice operations. His reputation for fairness and moral clarity earned him lasting respect.

Fighting for citizenship and civil rights

In his early years in the U.S. Saund faced several legal limitations. As a native of India, he was long prohibited from becoming a U.S. citizen. Refusing to accept this exclusion, he fought for change, not just for himself, but for the entire South Asian immigrant community.

As national president of the India Association of America, he lobbied, wrote, and spoke across the country for legislative reform. His advocacy culminated in the passage of the Luce-Celler Act of 1946, which allowed Indian nationals to become naturalized citizens. Saund played a crucial role in the grassroots movement that built momentum for the bill. The moment President Truman signed it into law; was both a political and personal victory for Dalip Singh Saund.

I came to this country (United States) with the glow of Abraham Lincoln’s words in my heart: ‘All men are created equal’.

Dalip Singh Saund

Naturalized in his fifties, Saund took his citizenship oath in December 1949 and almost immediately stepped into electoral politics. His rise from outsider to party insider was fueled by years of grassroots work, advocacy, and faith in the Constitution.

Making history with a seat in the U.S. Congress

By 1955, Dalip Singh Saund was a respected local judge and Democratic figure and a serious contender for national office. When Congressman John Phillips retired from California’s 29th District, Saund ran for the open seat. He beat party rival Karl Kegley in the primary and faced Republican Jacqueline Cochran Odlum, a celebrity aviator with powerful political connections.

Despite Cochran’s star power, Saund’s message resonated. He emphasized farm support, civil rights, balanced budgets, and diplomacy. He reminded voters of his American values, hard-earned citizenship, and commitment to fairness.

Everyone thought I had no chance but I had faith in the American sense of justice and fair play.

Dalip Singh Saund

He won by more than 3,000 votes. Saund’s victory made headlines worldwide. As a freshman Congressman, he was appointed to the House Foreign Affairs Committee. It was a rare honour. He used the platform to promote diplomacy, critique authoritarian regimes, and serve constituents tirelessly. He would go on to win reelection in 1958 and 1960 by large margins, championing civil rights, advocating for small farmers, and strengthening ties between the United States, Mexico, and India.

Dalip Singh Saund with the then US president John F Kennedy (left) and vice-president Lyndon B Johnson

The world takes note

In 1957, during his first term, Dalip Singh Saund toured Asia as an official House representative, visiting Japan, Taiwan, Vietnam, Indonesia, and India. Crowds greeted him like a hero in Amritsar and Chhajulwadi. In Vietnam, he criticized U.S. support for corrupt regimes, warning, “You cannot win hearts and minds by propping up dictators.” In Indonesia, he cautioned against charismatic authoritarianism. He brought the insights of a global citizen and former colonial subject to U.S. foreign policy debates.

A sudden silence

In 1962, while on a flight to Washington, Saund suffered a debilitating stroke. Though his family tried to keep up appearances, the truth emerged: he could neither speak nor walk unassisted. He was still nominated by the Democratic Party, but the seat went to Republican Pat Minor Martin. Though he regained some mobility, he never returned to public life. He died in 1973. Many believed that his political career might have soared even higher had he not suffered the life-altering stroke early in his bid for a fourth term.

Legacy beyond firsts

The trailblazer was a man of vision, tenacity, and grace under pressure. He never publicly complained about the racism he faced, choosing instead to model dignity, diligence, and democratic faith.

Dalip Singh Saund’s portrait was unveiled at the US Capitol, the building in Washington, D.C., where the United States Congress meets

He opened doors for generations of Asian Americans in the U.S. public life. His legacy lives in immigrants who found a home in America, nurtured by the seeds of change he helped plant.

ALSO READ: Rise of the Samosa Caucus in Trump 2.0: Indian American representation at its peak in 2025