(May 4, 2025) Long before bottled haircare products became commonplace, a Bihari migrant introduced Britain to the art of shampooing. It was not the quick rinse we know today, but a therapeutic amalgam of head massage and steam bathing. Sake Dean Mahomed, born in Patna in 1759, brought the Indian tradition of champi (a soothing head massage using fragrant oils) to the seaside town of Brighton, where his aromatic steam baths and revitalizing massages became all the rage among European elites. His services earned royal patronage, and the term ‘shampoo’ would eventually enter the global lexicon, evolving far from its roots into the bottled, detergent-based hair care ritual familiar across the world today.

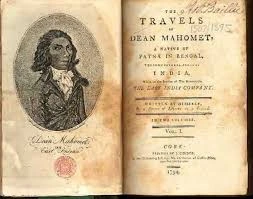

Mahomed’s influence stretched well beyond the bathhouse. He was the first Indian to publish a book in English. Titled The Travels of Dean Mahomet (1794) , it was a richly detailed narrative that offered British readers a rare glimpse into India through Indian eyes. One of the earliest Indian migrants to Europe, Mahomed also opened the Hindoostane Coffee House in London, the first Indian restaurant in Britain, inviting diners to experience the rich flavours of India.

From the Ganges to the English Channel, Mahomed’s life traced an arc of quiet influence. Through massage, memoir, and menu he bridged East and West and seeded traditions that led to the popularity of Indian food, and helped shape everyday habits globally.

Sake Dean Mahomed

Early life in Patna and military beginnings

Born in 1759 in Patna, a bustling city of the Bengal Subah under the Mughal Empire, Mahomed’s lineage has been debated. Some claim Shia Muslim roots with Arab-Turkic ancestry, while others place him in the Nai caste of barbers. What is certain, however, is that tragedy struck early. At just 11, Mahomed lost his father, a soldier in the Bengal Army, believed to have been recruited during British campaigns under Robert Clive.

He was soon taken under the wing of Captain Godfrey Evan Baker, an Anglo-Irish officer, who trained him as a surgeon in the East India Company army. For nearly 15 years, Mahomed traveled extensively across eastern and central India, participating in military campaigns against the Marathas and witnessing first-hand the cultural and geographical richness of his homeland.

Sake Dean Mahomed’s court dress in display at the Brighton Museum, UK

A new life in Ireland and England

In 1784, Mahomed accompanied Captain Baker to Cork, Ireland, where he immersed himself in local life and learned English at a local school. His marriage to Jane Daly, an Irish Protestant, was considered scandalous due to religious differences, but their union marked one of the earliest documented interracial marriages in Britain.

By 1794, Mahomed had firmly positioned himself in literary history. He published The Travels of Dean Mahomet, a 38-letter epistolary account recounting his military years in India, cultural encounters, and eventual migration to Europe. It was the first book ever written in English by an Indian, offering European readers an insider’s view of Mughal India, complete with vivid descriptions of Benares, Calcutta, and Indian military discipline.

Despite its narrative novelty, the book reflected Mahomed’s hybrid identity which was sympathetic to Indian customs but adopting a European voice and worldview. It didn’t criticize colonial misgovernance, rather introduced India’s richness to a curious Western audience.

Deen Mohamed’s book ‘The Travels of Deen Mohamed’

The Hindoostane Coffee House

In 1810, after relocating to London, Sake Dean Mahomed launched The Hindoostane Coffee House, one of his trailblazing ventures on George Street near Portman Square in London. This was the first Indian restaurant in England, predating Britain’s curry craze by over a century.

Catering to retired colonial officers and curious Londoners, the restaurant offered authentic Indian curries, hookahs with real chilm tobacco, and even home delivery service. It was a gastronomic portal into the subcontinent, and was lauded in The Epicure’s Almanack (Britain’s first restaurant guide, published in 1800s) for its unmatched curries.

Unfortunately, the venture folded in a couple of years of its launch due to financial troubles. Yet its cultural significance remains unparalleled. The blueprint of today’s £5 billion British-Indian food industry can be traced back to Mahomed’s vision.

The place where Hindoostane Coffee House was located

Adding eastern touch to British wellness by inventing shampooing

Following his culinary chapter, Mahomed pivoted towards a new enterprise that would redefine personal care and wellness in Britain, and that was shampooing. Inspired by the Indian practice of “champi”, Mahomed introduced Indian medicated vapour baths and therapeutic massage to the British elite.

In 1814, he moved to Brighton, a fashionable seaside resort, and opened Mahomed’s Baths, offering steam baths infused with herbal oils. This fusion of Ayurveda and spa treatment soon gained traction. Advertised as a cure for ailments ranging from rheumatism to stiff joints, the baths attracted Britain’s most influential patrons.

The business’s meteoric success earned him the nickname “Dr. Brighton”, and Mahomed became the official shampooing surgeon to King George IV and William IV. His wife, Jane Daly, also supervised the ladies’ section of the bathhouse which was an early example of family-run diaspora enterprise.

Mahomed authored two additional books to promote his treatment: Cases Cured by Sake Deen Mahomed (1820) and Shampooing: Benefits Resulting from the Use of the Indian Medicated Vapour Bath (1822). These works, which underwent multiple editions, reflected the confidence and entrepreneurial spirit that defined his career.

Mahomed’d Bathhouse in Brighton

Family, faith, and complexity

The multifaceted entrepreneurs’s personal life was as layered as his career. He converted to Christianity in 1786, likely a move to integrate into European society. He fathered children with Jane Daly, and possibly also with another woman, Jane Jeffreys, leading to accusations of bigamy. It’s a fact confirmed by parish records from Marylebone.

His descendants continued his legacy of public service. His son Frederick ran a bathhouse and fencing school in Brighton. His grandson Frederick Akbar Mahomed became a physician of international renown, contributing to early studies on hypertension. Another grandson, Rev. James Keriman Mahomed, served as a vicar, and their children eventually anglicized their surnames during World War I to avoid xenophobic backlash.

Death and rediscovery

Sake Dean Mahomed passed away in 1851 in Brighton at the age of 91, a respectable age for any era. He was buried at St Nicholas Church in Brighton. Despite his celebrated life, his name slowly faded from public memory. For much of the 20th century, his achievements were known only to niche scholars.

Sake Deen Mahomed

However, that changed in the 1970s and 80s with the revival of interest by poet Alamgir Hashmi and historian Michael H. Fisher, who published The First Indian Author in English (1996). His name also featured in Rozina Visram’s Ayahs, Lascars and Princes, a landmark history of South Asians in Britain.

Commemorations and Google’s global tribute

In recent years, Mahomed has reclaimed his rightful place in diaspora history. In 2005, the City of Westminster installed a Green Plaque on George Street to mark the site of the Hindoostane Coffee House. In 2019, Google honoured him with a Doodle on the 225th anniversary of his book’s publication, introducing him to a global audience once more.

His writings were also included in The Book of Bihari Literature, curated by diplomat Abhay Kumar, celebrating the literary heritage of the state of Bihar, Mahomed’s birthplace.

A diaspora trailblazer ahead of his time

Sake Dean Mahomed embodied the hybrid identity of early global Indians. He was a cultural ambassador, long before the term became fashionable. Whether it was cuisine, wellness, or literature, he infused Indian traditions into British life transforming public tastes and perceptions.

He remains an icon of early Indian diaspora resilience, navigating colonialism’s power structures while asserting his identity through innovation. Today, as Indian-origin entrepreneurs and cultural figures thrive globally, Mahomed’s story is a powerful reminder of those who paved the way.

More than two centuries ago, long before the world spoke of ‘soft power,’ Sake Dean Mahomed showed how it can flow through a bowl of curry, a soothing massage, or a well-penned memoir.

ALSO READ: Sophia Duleep Singh: The Indian princess who took on the British Empire for women’s rights