(August 31, 2025) When India stood on the brink of independence and then stepped into the world as a newly independent nation, the West still dismissed it as a land of fakirs and snake charmers. Magician P.C. Sorcar turned those stereotypes into spectacle. For his oriental attire, foreign newspapers often likened him to a figure out of the Arabian Nights. Whether cutting a woman in half on a live BBC show in the UK, making his assistants float in mid-air in Tokyo, or parading elephants in Paris, he made India a synonym for wonder, performing to packed theatres across Asia, Europe, North America, Australia, Africa, and the Middle East. He transported his audiences into a world of exoticism and enchantment through the art of magic, and the flair for presentation through the costumes, the drama, and the showmanship.

PC Sorcar during one of his shows, performing against an elaborate stage backdrop

On an ordinary Monday evening in April 1956, British families tuned into Panorama, the BBC’s flagship programme. What they witnessed was chaos. A turbaned Indian magician placed a young woman into a trance, laid her on a table, and appeared to slice her body in half with a roaring buzz saw. When he tried to revive her, she remained motionless. The camera cut, the credits rolled, and Britain panicked.

The BBC’s switchboard lit up with frantic calls: Was the girl dead? Had they really watched a killing on live television? The next morning’s newspapers screamed: “Girl cut in half – shock on TV.” For Protul Chandra Sorcar, the man behind the illusion, this was no mishap. It was his masterstroke. With one perfectly timed performance, P.C. Sorcar had stunned Britain, sold out his season at the Duke of York Theatre, and stamped Indian magic onto the world stage.

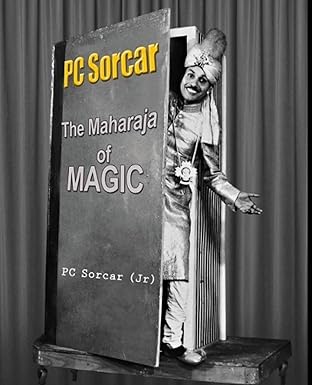

But this was not his first step abroad. By the mid-1950s, Sorcar was already a seasoned international performer. Since the late 1930s, he had built a reputation across Asia, especially in Japan, Burma and Malaya, where his Indrajal shows blended Indian imagery with modern stagecraft. During the colonial years, Sorcar refused to perform in the UK. “He hated the idea of entertaining the enemy land,” his son P.C. Sorcar Jr. recalled in his book, PC Sorcar: The Maharaja of Magic. When he finally went to London in the 1950s, it was not as a colonial subject begging for recognition but as the “Maharaja of Magic”, representing a proud, newly independent India before audiences who had once sneered at Indian conjurers as fakirs and tricksters.

A boy with two callings

Born in 1913 in Ashekpur, Tangail (now Bangladesh), Protul was raised in modest surroundings. At school, he was considered a prodigy in mathematics, solving complex problems that baffled older students. His teachers expected him to pursue academics, and he eventually earned a B.A. in mathematics at Ananda Mohan College.

But alongside equations, another obsession grew. Village conjurers and street performers fascinated him. Where others gaped at a disappearing coin, Protul scrutinized the sleight of hand, trying to reverse-engineer every move.

His role model was Ganapati Chakraborty, Bengal’s pioneering magician. Protul followed him into theatres and circuses, learning by watching. Against his family’s wishes, he began performing as a teenager at local fairs, shocking relatives who thought magic was “cheap” and “undignified.” He would later explain, “Magic is not superstition. It is art. It is science. And India must show it to the world.”

Subhas Chandra Bose and the patriotic magician

At Saraswati Press, a hub for intellectuals in Calcutta, Sorcar met Subhas Chandra Bose. Bose admired Protul’s defiance. Here was an educated Bengali youth who refused the security of a colonial clerkship and instead chose the uncharted path of a magician. Sorcar, in turn, was drawn to Bose’s magnetism and nationalist zeal.

He began raising funds for the movement through his shows, sometimes even carrying secret papers tucked into his magic boxes. When he spoke of his dream to perform overseas, Bose offered counsel that would change his destiny. “It won’t be any good going to England,” Bose warned. “They will never give an Indian his due respect. Better go to Japan. They value talent.”

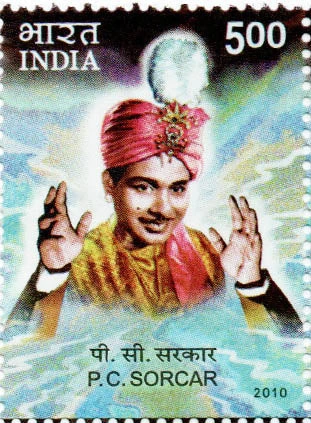

Indian stamp honouring PC Sorcar

Establishing his magic against all odds

In 1937, Sorcar obeyed. He booked passage on a rusting cargo ship bound for Kobe, a journey he could barely afford. His ticket was “deck class,” meaning no cabin, no comforts, just an open berth under the elements. With him, he carried a battered wooden trunk filled not with clothes but with the precious props for his magic shows.

Midway across the Pacific, a storm broke out. The deck pitched violently, waves battering passengers into corners. Crewmen barked at the deck-class travellers to abandon their baggage if they wanted to come inside and survive. Fellow passengers pleaded with Protul to let go of his battered trunk. He refused. “My life is in this box,” he said simply, clinging to it as the ship heaved through the night. By the time they reached Kobe, the ordeal had broken him, he was in fever. The trunk was gone, swept into the sea. His visa and papers had vanished with it. Feverish, exhausted, and penniless, he staggered onto Japanese soil with nothing but the clothes that he was wearing.

To the immigration officers, he was just another stranded foreigner with a dubious story. He pleaded that he had come to perform magic shows, but without props or papers he was admitted only as a tourist, forbidden to work. For days he wandered, relying on the hospitality of a few Indians living near the port.

Then came a chance, at a gathering of the Kansai Magicians’ Club in Kobe. Sorcar was invited more out of curiosity than as a guest. The local magicians eyed him with suspicion. He had no props, no costumes, no reputation. Just his bare hands.

When the moment came, he asked for a handkerchief, a coin, and a piece of paper. Within minutes, he had the room in thrall. Coins vanished and reappeared in pockets. A borrowed handkerchief turned into a bird. His sleight of hand was lightning-quick, and his presentation was theatrical. The skeptics erupted in applause. They gave him money, pressed contacts into his hands, and promised him shows.

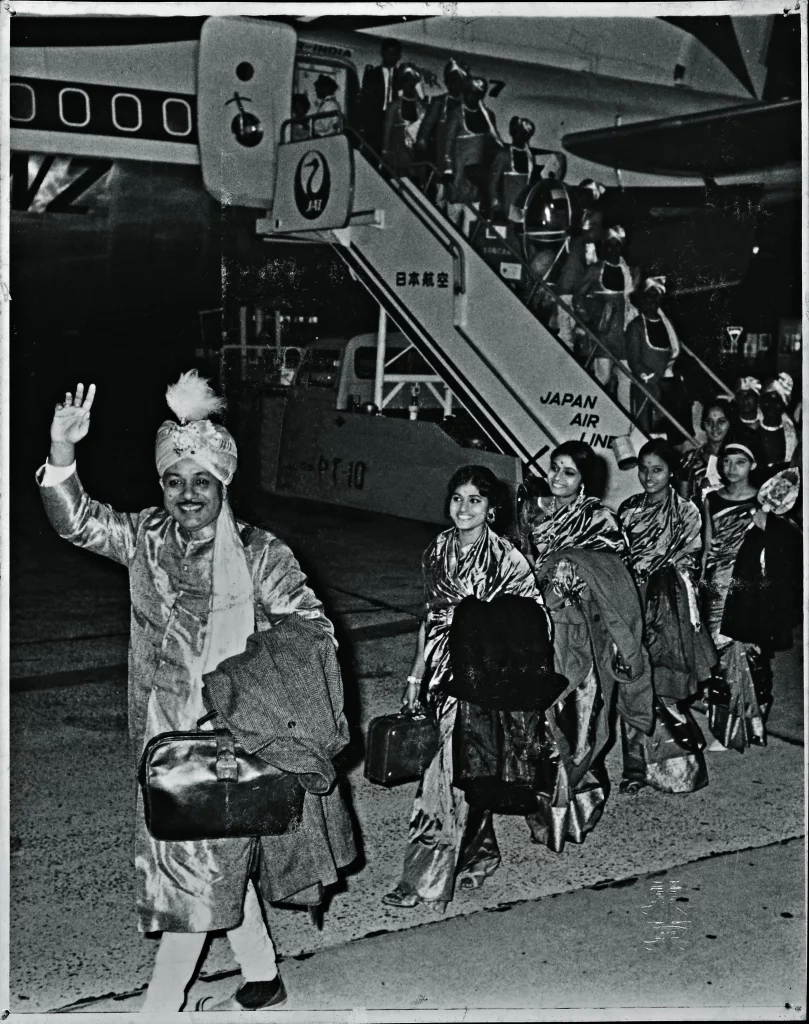

Outside the venue of one of PC Sorcar’s shows abroad

From that fever-ridden, prop-less beginning, Sorcar’s career in Japan took flight. He performed in Kobe under the joint auspices of the Japan–India Society and the Federation of Buddhist Associations, and later in Tokyo with help from Rash Behari Bose and other Indian nationalists living there. The Japanese press praised him; crowds flocked to see the young Bengali who could conjure miracles with nothing more than his hands.

That storm-tossed voyage and triumphant debut in Kobe became the crucible of his identity. Protul Chandra Sorcar was no longer just a curious boy from Tangail; he was an Indian who could turn disaster into spectacle, carrying his country’s pride onto foreign stages. He started performing across continents, dazzling audiences in Asia, Europe, North America, Australia, Africa, and the Middle East, carrying India’s magic onto the world stage.

Indrajal: The magic of India

By the late 1930s, Sorcar had created his signature travelling show: Indrajal. The name, from Sanskrit, meant “the net of Indra,” a metaphor for illusion.

Indrajal was a theatre on an epic scale. Painted backdrops resembled temples and palaces. Costumed assistants floated, vanished, or were sawed in half. Elephants marched at the entrance. He introduced signature acts like the ‘Water of India – a jug that poured endless water,’ ‘The Floating Lady – an assistant levitating in midair’, ‘The Drum Illusion – a woman vanishing inside a giant drum,’ and ‘X-ray Vision – reading writing on a board while blindfolded.’

In Paris in 1955, Indrajal premiered to sold-out crowds. Theatres were fronted with Taj Mahal facades, and elephants greeted spectators. French critics called it “a revelation.” For the first time, Indian magic looked as sophisticated as any Broadway show.

“He took Indian magic where it had never gone before,” wrote historian David Price. “With Sorcar, Indian magic had come of age.”

PC Sorcar during one of the shows depicting a scene on the surface of the moon

The BBC coup

Television was Sorcar’s greatest gamble. In April 1956, on BBC’s show Panorama, he performed sawing a woman in half. He timed it so that just as the saw seemed to slice through his assistant, the programme abruptly cut off.

Britain went into meltdown. The next day The Daily Mirror reassured readers with a smiling photo of assistant Dipty Dey: “Alive and well — and ready to be cut in half again.”

His London season sold out. Rivals seethed, critics gasped, and Sorcar had achieved the impossible. He had made Indian magic headline news in Britain.

Family and final illusion

Behind the flamboyance was a family man. At home in Calcutta, he shed sherwanis for a simple dhoti, playing with his children. His wife Basanti Devi was his emotional anchor, though she worried constantly about his health.

As his tours grew longer, she feared each departure. In 1970, when doctors warned him against travel, she begged him to stop. But he refused. “Magic is my duty — to India, and to the world,” he told her.

On January 6, 1971, soon after performing in Shibetsu, Hokkaido in Japan, he collapsed backstage with a heart attack. His final exit seemed an illusion in itself.

The robes passed on

The curtain could have fallen. But the Sorcar legacy demanded otherwise. His young son, P.C. Sorcar Jr., donned his father’s flowing robes, trembling before the crowd in subsequent shows. “It was terrifying,” he admitted in his book. “But I knew my father’s last wish was that magic must live on as India’s pride.”

Jr. PC Sorcar went on to become a global magician, cementing the Sorcar dynasty. His daughters and grandchildren also carried the tradition, from stage to laser art.

The patriotic Indian

P.C. Sorcar’s journey encompassed more than tricks and illusions. It consisted of the audacity of choosing an unconventional career, patriotism, and cultural diplomacy. He saw magic as science and art, and turned colonial caricatures upside down, presenting India not as land of fakirs but of masters.

PC Sorcar and his entourage on an international tour

“Keep up this rage,” Bose had told him once. “One day it will take you to the top of the world.” And so it did.

More than tricks and theatre, his illusions carried meaning. With every act, Sorcar created not just wonder, but a new identity for India in the eyes of the world.

ALSO READ: 100 Years of Raj Kapoor: The showman who won hearts in Russia and beyond