Name: Vedant Harlalka

University: University of Toronto

Course: Bachelor’s in Electrical and Computer Engineering

Location: Canada

Key Highlights:

- Recipient of the Lester B. Pearson International Scholarship, awarded to only 37 students globally each year.

Determined to pioneer advances in quantum, bio, and analog computing to overcome the limits of current hardware.

Diverse, discussion-driven classrooms where students tackle real-world problems.

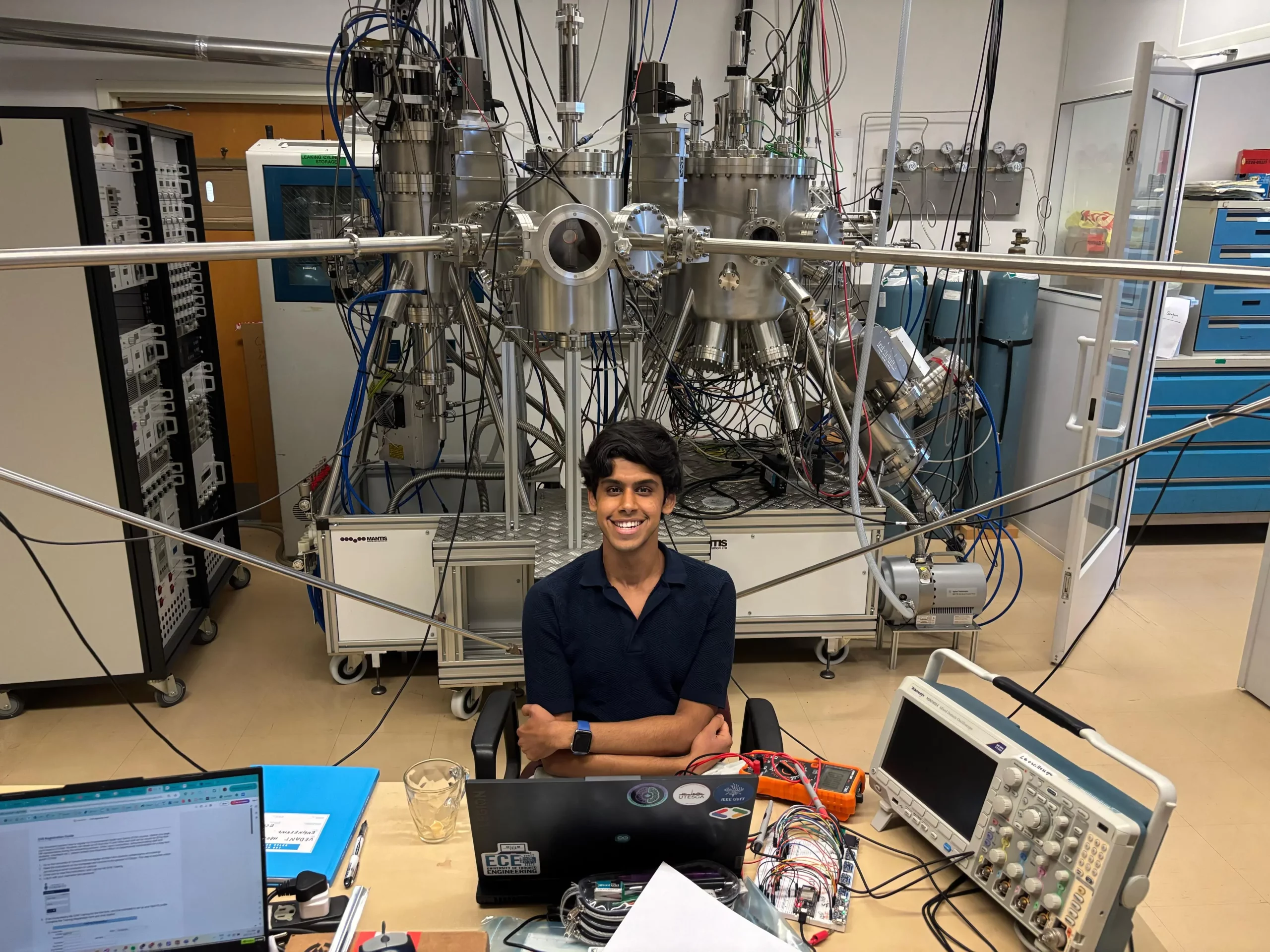

(August 20, 2025) When 19-year-old Vedant Harlalka was deciding where to study, he knew he wanted more than just a top-ranked engineering program — he wanted to be in a place that could give him both cutting-edge technical training and a truly global perspective. Today, he is pursuing a Bachelor’s in Electrical and Computer Engineering at the University of Toronto on the prestigious Lester B. Pearson International Scholarship—a full-ride worth nearly CAD 400,000.

Vedant Harlalka

“It covers tuition, accommodation, meals, and even a stipend for incidental expenses,” Vedant explains. “Only 37 students across the globe are selected each year. But the real value lies in the community — it’s a network of people who’ve built multi-million-dollar startups or are working at top companies like Google and NVIDIA. The university actively nurtures this network through socials and mentoring events,” he tells Global Indian.

Why Canada for Engineering

Vedant’s choice of Canada — and the University of Toronto — was shaped by both ambition and perspective. “University of Toronto is the birthplace of AI and home to Nobel laureates like Geoffrey Hinton. For someone determined to redefine the future of computing hardware, this is where I needed to be,” he says.

His passion is rooted in a challenge few outside the tech industry talk about. “The biggest hurdle humanity faces in computing right now is the size of transistors — the basic building blocks of computers. For decades, shrinking them has made our devices faster. But we’ve hit a point where they can’t get any smaller. That means current hardware won’t support the problems of tomorrow.”

He believes the next technological revolution will be in hardware. “We’ve had a massive software boom over the last 15 years. Now, I expect the same in hardware. Just a couple of years ago, you could run applications like Word or Excel locally on your device. Today, even a neural network like ChatGPT has to run on massive servers that consume huge amounts of water and electricity. I want to work on quantum computing, biocomputing, and analog computing to break this bottleneck.”

Canada’s diversity was another draw. “In one of my first classes, we were split into teams with students from Africa, the US, Europe, and the Caribbean to solve real-world problems. Everyone brought a completely different way of thinking. That diversity isn’t just enriching—it’s essential to building technology that works for everyone.”

The Journey to the Pearson

Winning the Lester B. Pearson Scholarship took more than academic brilliance. “Grades are just the entry ticket. What truly matters is what you do beyond the classroom,” Vedant says.

In his case, that meant inventing one of India’s most economical 3D printers and delivering guest lectures on entrepreneurship and innovation at schools and engineering colleges. But the road to U of T wasn’t just about achievements — it was about navigating a rigorous application process. “You need your marksheets, SAT score, and letters of recommendation — one from your school and one from an external referee. Then there are the essays, where they gauge your personality and interests through your extracurriculars. What they are looking for is a jack of all and master of one.”

Vedant recalls managing all this while preparing eight hours a day for the IIT-JEE in his final years of school. “I couldn’t afford a career counsellor, and the entire process took a huge emotional toll. What made it easier was the help I received from seniors who had gone through it before me.”

That experience shaped one of his core commitments today. “After getting into the University of Toronto, I decided I’d give back. I now mentor juniors in India who are applying abroad. I know how overwhelming it can be when you don’t have anyone to guide you, and I want to make sure they don’t face the same struggle.”

The Leap to a New Continent

His first transatlantic flight was both exciting and exhausting. “Twenty-four hours without internet was… an experience,” he laughs. But the moment he landed, the support system kicked in. “The university arranged my airport pick-up, organised cultural transition programs, and introduced me to student clubs—including a vibrant desi student association. The people here are incredibly welcoming and open to all cultures.”

In those first weeks, Vedant found himself in conversations that left a mark. “I’ve had some of the best discussions in the residence dining hall with students from every corner of the world. We talk about our cultures, swap ideas, and challenge each other’s perspectives.”

Learning That Goes Beyond the Textbook

The biggest academic shift for Vedant was the change in philosophy. “In India, you’re taught to solve questions correctly. Here, you’re taught to ask the right questions,” he says. “Professors give you open-ended, real-world problems, and you’re graded on your process — the assumptions you make, the creativity you show, and how you reach your conclusions — not just on the final answer.”

One of his favourite examples comes from his Linear Algebra class. “We had an assignment to find the longest and shortest shadow of the CN Tower in Toronto. In the real world, there isn’t a single correct answer, so they looked at how we approached the problem rather than what number we arrived at.”

Courses like Engineering Strategies and Practices also reflect this approach. “They put you in diverse teams and give you global problems to solve. The whole team gets the same grade, based not only on the technical solution but also on communication, collaboration, and how effectively you identify and address stakeholder needs.”

Specialist instructors bring in skills that go far beyond engineering theory. “We have communication coaches who train us to conduct client meetings, create effective presentations, and speak confidently in public. There’s also a teamwork coordinator who teaches us frameworks for professional collaboration. You can be the best engineer in the world, but if you can’t communicate your ideas, it’s meaningless.”

There’s also an unusual freedom to learning. “We have a zero per cent attendance policy because the philosophy is that if you have somewhere more important to be, you should be there. Despite that, the classrooms are always full — after all, we’re being taught by Nobel laureates and the authors of our textbooks.”

Why Diversity in Tech Matters

For Vedant, diversity isn’t just a nice-to-have — it’s a fundamental requirement for building technology that truly serves everyone. “When you have people from different cultures and backgrounds in the same room, you bring together multiple ways of thinking. That’s not just enriching — it can completely change the outcome of a project,” he says.

He points to a striking example from everyday life: infrared motion-sensor taps. “These were mostly developed in North American labs by predominantly white engineers. The sensors are excellent at reflecting infrared radiation from light skin, so they work perfectly for that demographic. But with darker skin, which absorbs more infrared radiation, the taps often fail to detect a hand. It’s a simple but powerful reminder that technology designed without diversity can unintentionally exclude large parts of the world’s population.”

This is why his classes at the University of Toronto intentionally mix students from across continents. “In one project team, I had classmates from Africa, the US, Europe, and the Caribbean. We had to solve a global problem together, and everyone’s cultural background shaped how they approached it. You see first-hand how varied perspectives lead to more inclusive and innovative solutions.”

For Vedant, the goal is clear: “We need engineers who can design for the entire planet, not just a fraction of it. Diverse teams make that possible.”

Opportunities Without Limits

Vedant’s work on campus isn’t confined to lectures and assignments. “The University of Toronto has engineering design teams and clubs for almost everything — from robotics to clean energy,” he says.

One of his most active involvements is with the IEEE Tech Team — part of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, the world’s largest technical professional organisation dedicated to advancing technology. “Through the IEEE Tech Team, we built a bionic arm entirely from scratch. It can be used in medical applications or in labs where hazardous materials are handled, taking on the risky work by mirroring a human’s movements.”

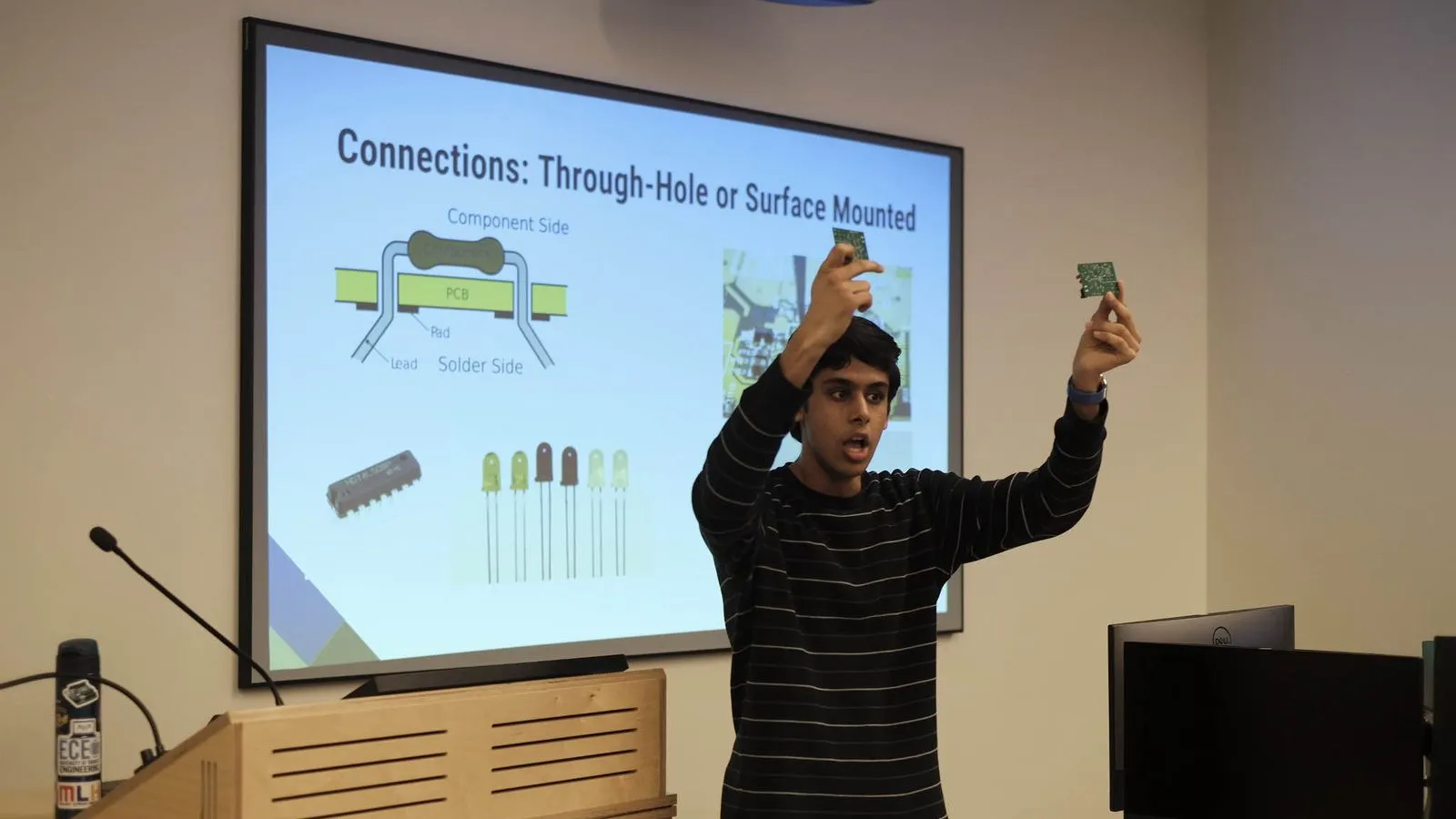

He also delivered a lecture on circuit design for the IEEE Tech Club, helping students build their own robots, circuits, and devices. Another highlight was joining the Machine Intelligence Student Team. “They sent me to the Rotman School of Management for a workshop on predicting buy and short calls in the stock market using AI. Teaching business students computer science in just two hours was challenging, but it pushed me outside my comfort zone and made me a better communicator.”

As a Laidlaw Scholar, Vedant is now researching nanomaterials and sustainable building systems. “In summer, you want sunlight without the heat; in winter, you want to retain warmth. We’re designing adaptive window systems to make that possible. Next year, I’ll spend six weeks in an underserved part of the world to create real-world impact at the ground level.”

Traditions, Adventures, and Life Lessons

Vedant still remembers walking into his first week on campus — or Frost Week, as it’s fondly called. “It makes the entire university feel like home,” he says. The week is a mix of formal ceremonies and quirky traditions unique to Canadian universities.

It begins with the matriculation ceremony — “it’s a mix of skits and formal addressal on the traditions and culture,” — and is followed by the Purple Dye Ceremony, where all first-year engineering students jump into huge buckets of purple dye. “It has its significance. During World War II, engineers were made to wear purple armbands on their uniforms and most of them worked in the most brutal conditions like boiler rooms of a ship or a hot room of an incinerator or a factory, and in sweating conditions, the purple dye would leave a mark on their uniform. Many engineers went out to sea and unfortunately many went down in wars and engineers have to be the last ones to leave as they tried to keep it up.”

Another tradition that resonates deeply with him is the Iron Ring Ceremony, akin to a graduation rite. “You are made to put on an iron ring — the significance of which is dated back to many years ago when a bridge in Quebec fell down due to engineer’s dishonesty. So each year, during the graduation ceremony, you are made to put on an iron ring made from the same fallen bridge as a reminder of your responsibility as an engineer.”

Outside the classroom, Vedant spends his weekends exploring the outdoors — kayaking, biking across Ontario, or trekking with friends. “I love being outside and having adventures with different people. It’s a blast to learn so much,” he says. But striking the right balance has been a challenge. “I initially began by brutally scheduling my Google Calendar but it takes a toll on your mental health. So I realised more than scheduling activities, it’s so important to schedule breaks and gym time. That was one big learning.”

Looking to the Future

Vedant’s long-term goal is clear. “I plan to spend some time in North America before returning to India to start a venture in semiconductor research, AI, or battery technology. The skills I’m building here are invaluable to my country. Sitting in this privileged position, it’s my responsibility to go back and contribute.”

His advice to aspiring students is simple but powerful: “Have an insatiable hunger for knowledge. Never stop asking questions. Stay curious about everything. The most successful students I’ve met share three traits: a bias for action, clear thinking, and the courage to challenge the status quo.

- Follow Vedant Harlalka on LinkedIn

Proud of you, Vedant